- عربي

-

- share

-

subscribe to our mailing listBy subscribing to our mailing list you will be kept in the know of all our projects, activities and resourcesThank you for subscribing to our mailing list.

How the Many Become a Few

The great reduction of Lebanon’s foreign donors

1Throughout its post-civil war period, a plethora of countries and institutions have supported Lebanon’s economic, institutional, and social development. This development assistance granted essential resources to state institutions that Lebanese governments could not provide themselves. Today, the overlapping crises have further decimated the government’s abilities to finance even the most necessary of developmental projects, from maintaining roads to upgrading electricity provision. At the same time, however, many donors have withdrawn their development assistance to state institutions amid prolonged political paralysis.

This article is part of a series which analyzes a new dataset of all loan and grant agreements that Lebanon’s governments accepted after the civil war. This dataset, collected and generously made available by Gherbal Initiative, provides details of all loans and grants pledged by bilateral (states) or multilateral (international organizations) donors to state institutions that are recorded as a law or decree and published in the Official Gazette. This dataset includes information on the pledged amount of each loan or grant, the donor, the administration to which it is donated, the sector it targets, as well as the dates of the agreements.2 With these details, this dataset provides the first comprehensive overview of the patterns by which governments solicited – and donors offered – international assistance to Lebanon after its civil war.

After examining the composition of loan and grant agreements during various presidential and governmental periods in a previous contribution, this article maps out the major donors that have supported Lebanon’s government institutions since 1990, as well as the sectors they have prioritized. We make two main observations. First, donors have prioritized the security sector by pledging the largest amounts of grant agreements to institutions like the Lebanese Armed Forces. The water and transportation sectors follow, albeit supported mostly with loans. Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries as well as European Union institutions and countries emerged as the main donors, pledging the largest amounts of support.

Second, of the many donors that supported Lebanon after its civil war, only a few remain today. Since October 2019 and the government’s default on sovereign debt in March 2020, few countries and organizations still provide financial support to government institutions amid a paradigm shift of donor assistance to support humanitarian programs and non-governmental institutions. GCC countries in particular have almost entirely withdrawn support since 2016, after having been the main donors in the periods following the withdrawal of Syrian troops in 2005. In that way, financial assistance significantly declined, leaving the World Bank and the European Union as nearly the only institutions to provide financial assistance via state institutions.

Security as donors’ key priority

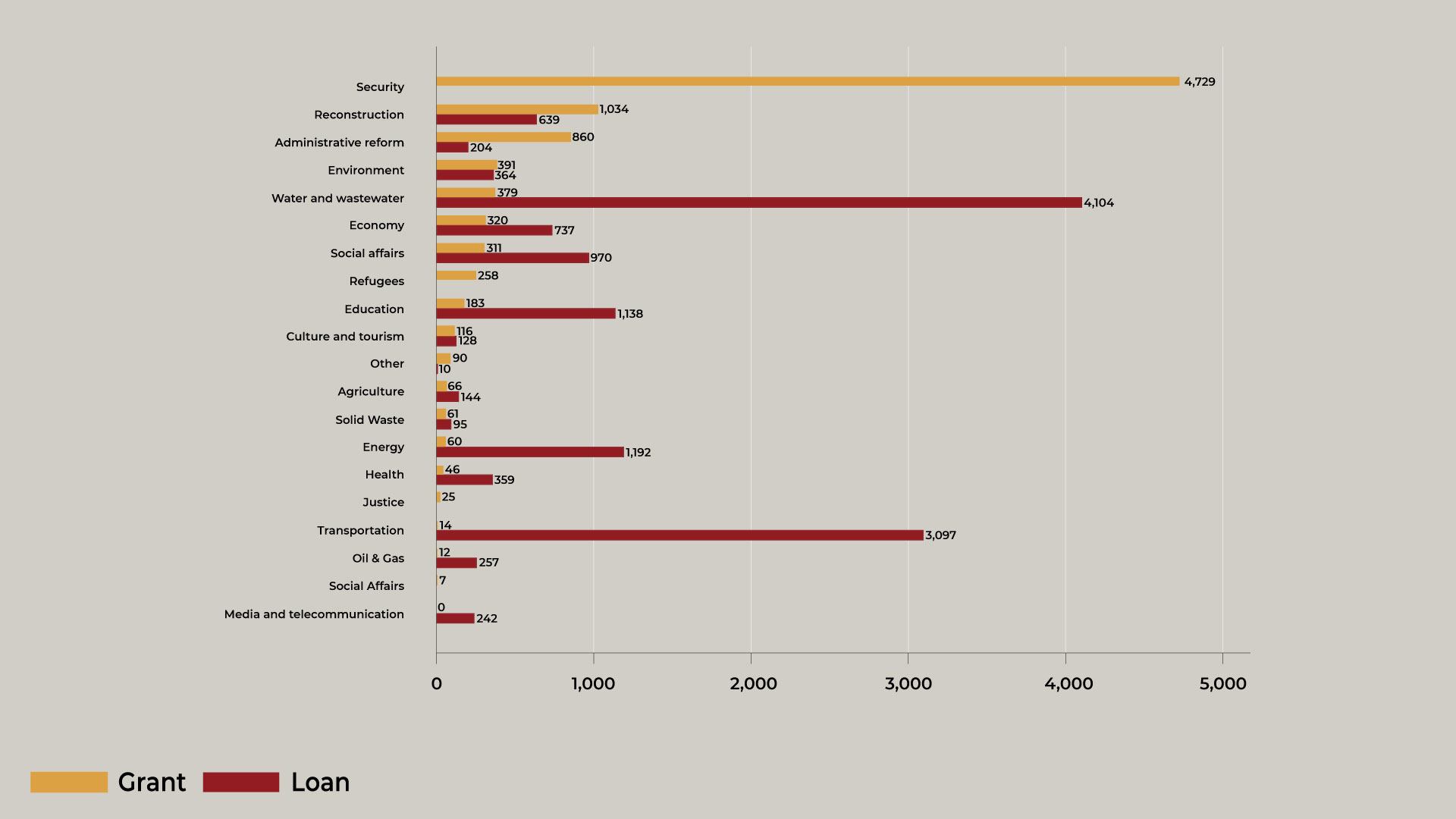

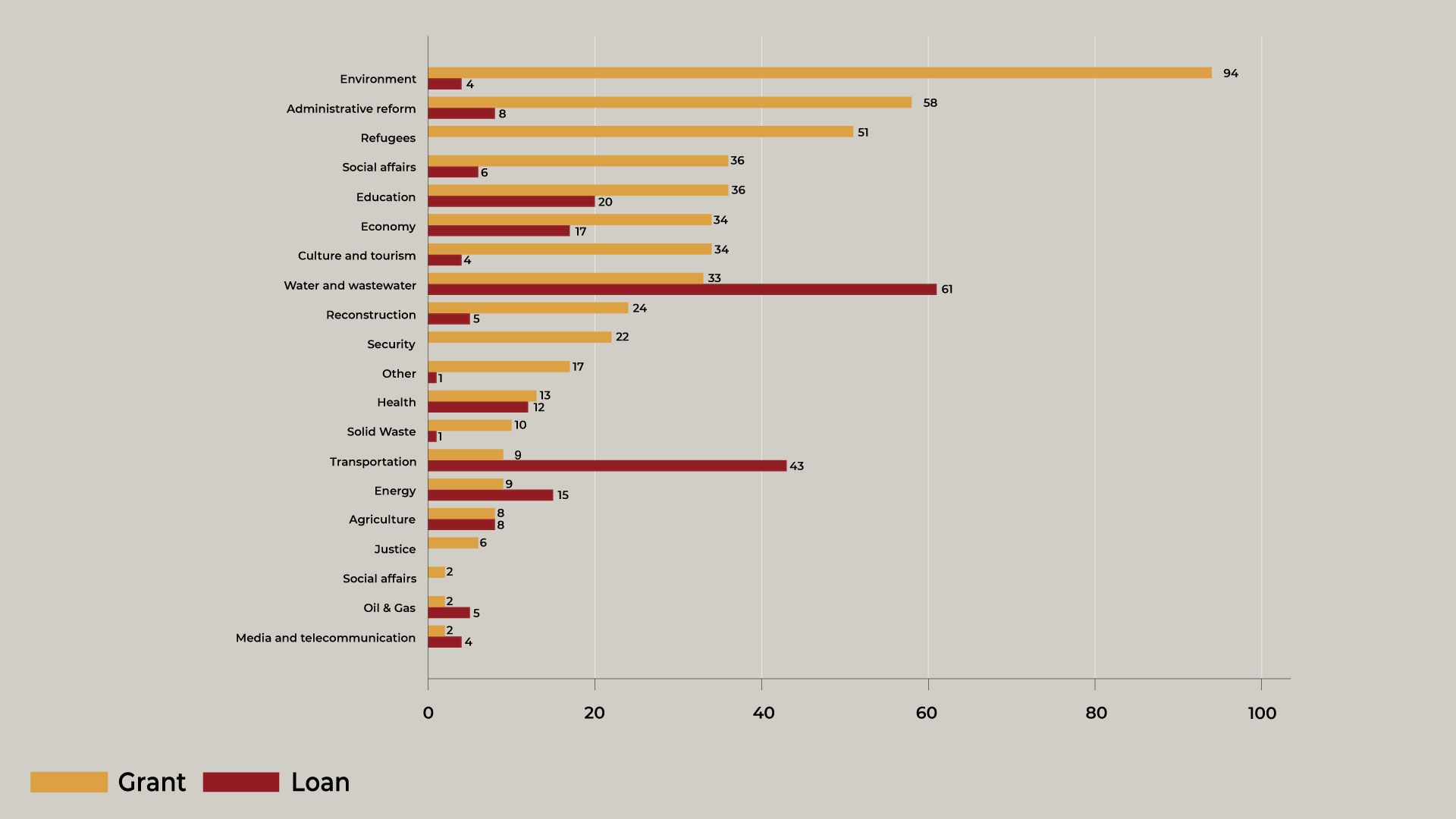

Grants and loans issued by international donors concentrate on a few notable sectors. In terms of grants, donors prioritized the security sector and issued it by far the largest share of pledges, almost $5 billion (all amounts in 2021 real values), while environmental projects as well as technical assistance for administrative reform received the highest number of agreements (94 and 58) (figure 1). Several grants were directed to support refugees, both Palestinian and Syrian, but the resources these grants provided ($258 million) were limited compared to the funds provided to other sectors.

Regarding loans, projects in the water and wastewater, as well as transportation sectors, were provided with the most funding ($4.7 and $3 billion) as well as the largest number of individual agreements (61 and 43). For sectors such as environment, culture and tourism, or solid waste, governments solicited only a few loan agreements. For refugees, social affairs, the security sector, as well as the justice sector, governments solicited no loans.

Figure 1: Amount (upper, in million US dollar) and number of loan and grant agreements

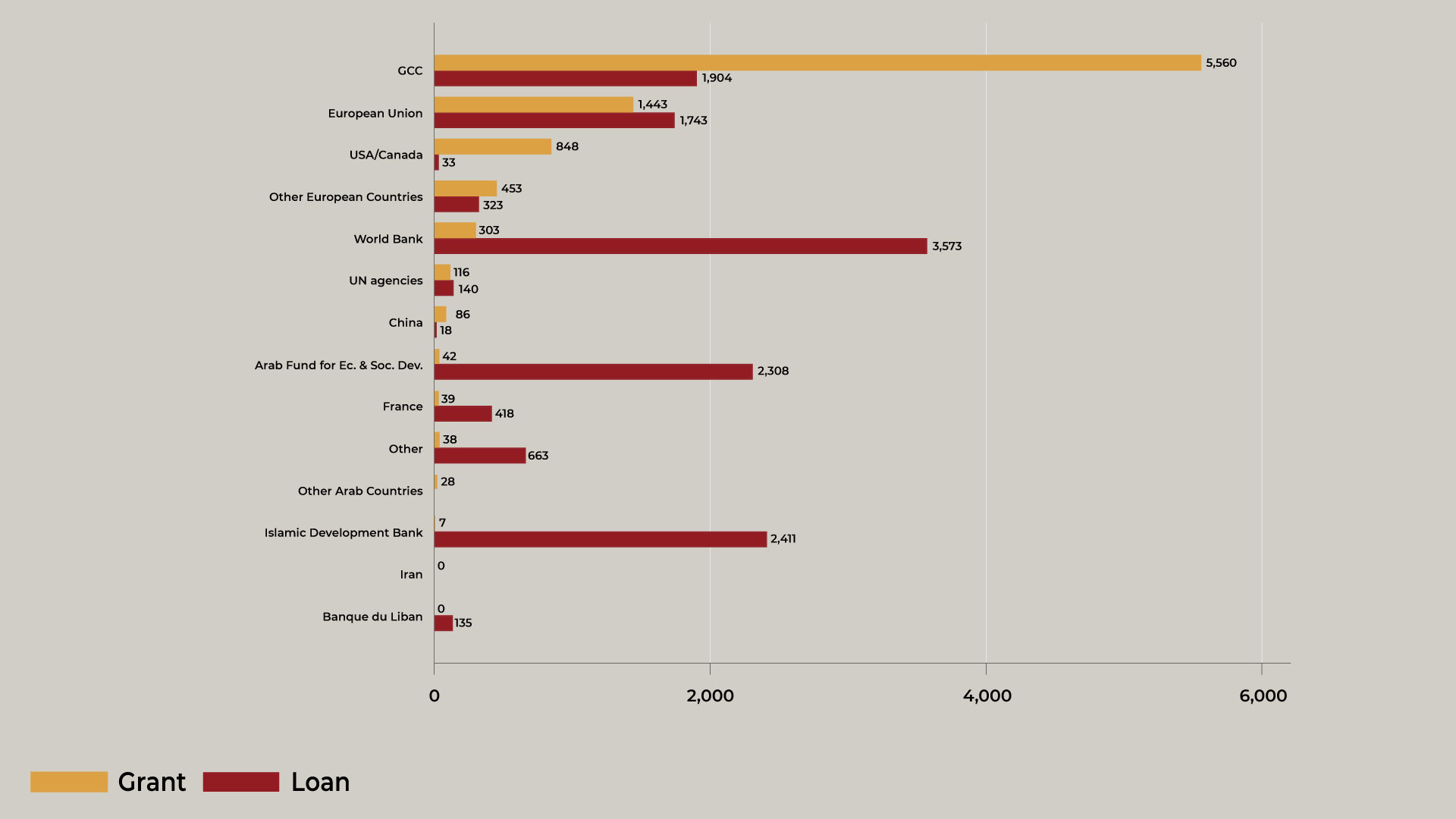

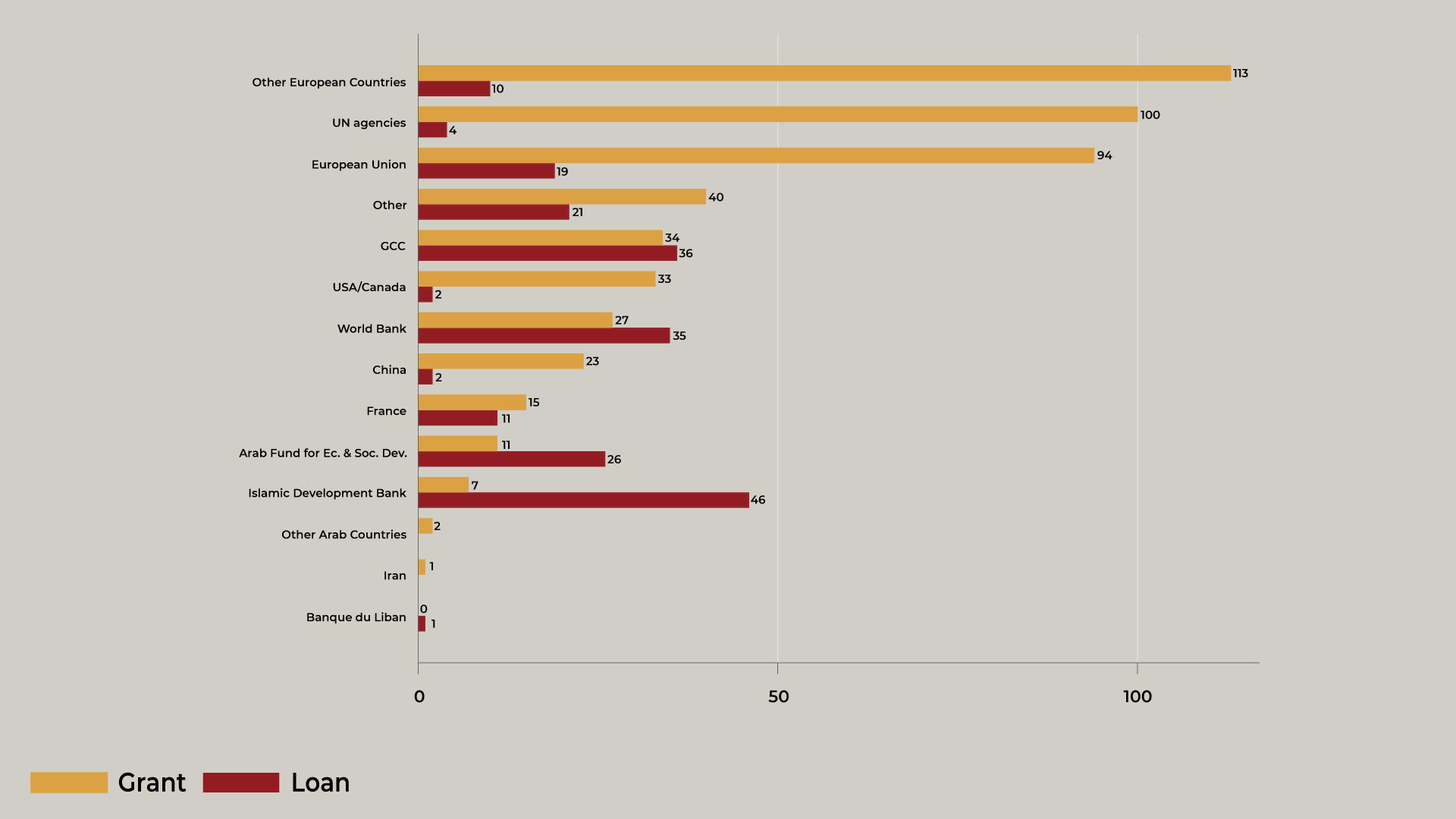

GCC countries, notably Saudi Arabia, are the largest grantors (figure 2). For example, in 2014, Saudi Arabia pledged $3 billion and $1 billion for “arming and equipping the army, internal security forces, public security, and state security”, which was granted to both the Ministry of Defense and the government. While both grants appear not to have been disbursed, GCC countries remain the largest donors, even without these two large grants. In total, Saudi Arabia alone has donated almost $5 billion in official assistance since 1991. Other large donors are the European Union with about $1.4 billion, the United States with about $0.8 billion, and individual European countries with almost $0.5 billion. In terms of loans, the World Bank ($3.5 billion), the Islamic Investment Bank ($2.4 billion), the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development ($2.3 billion), and the European Union ($1.7 billion) have provided the largest amounts. With 222 grant agreements, individual European countries and the European Union itself signed the largest number of individual agreements. Other Arab countries (excluding GCC) provided two grants, while Iran provided only one.

Figure 2: Amount (upper, in million US Dollar) and number (lower) of agreements by donor

The great reduction – only few remain

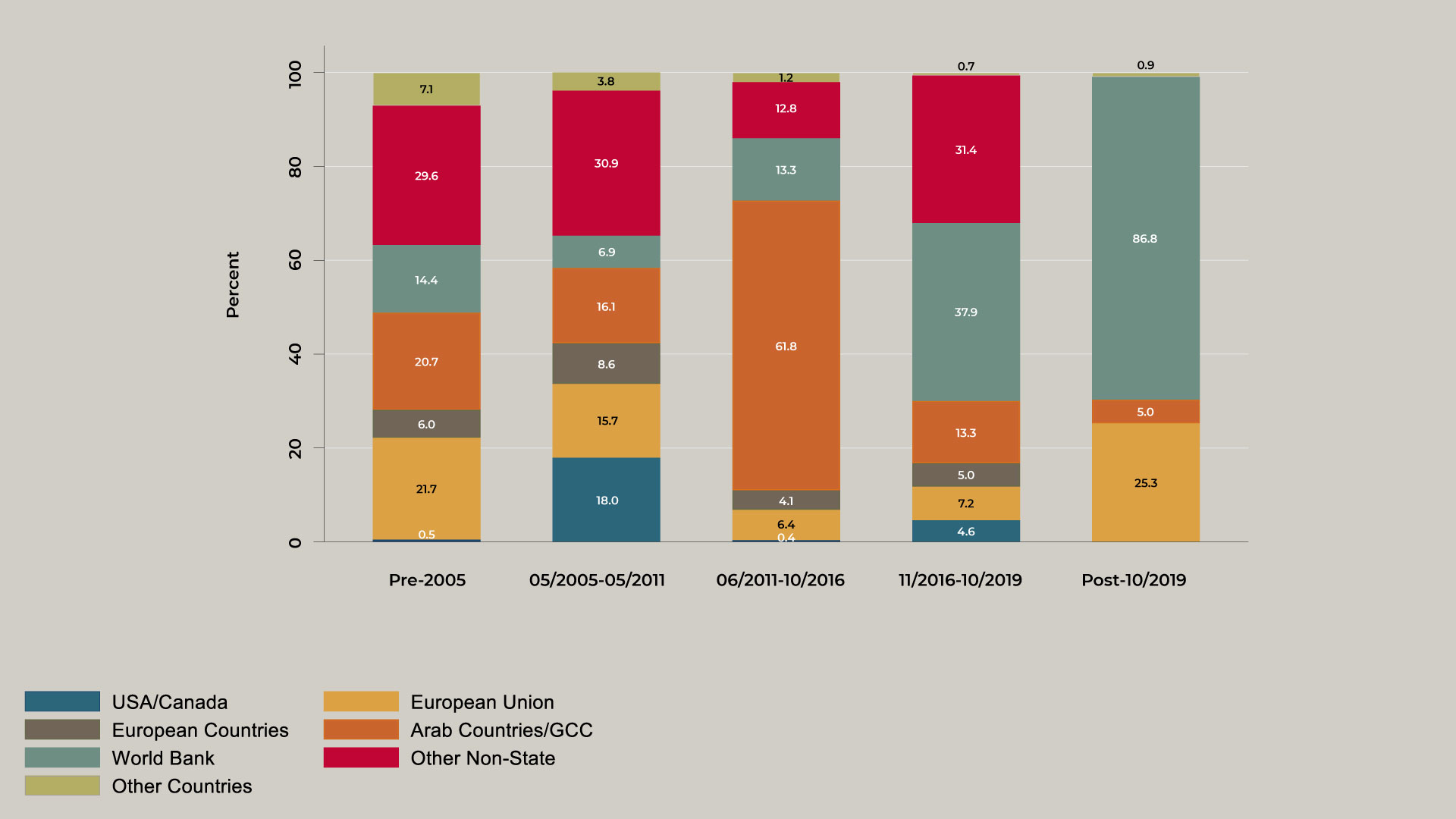

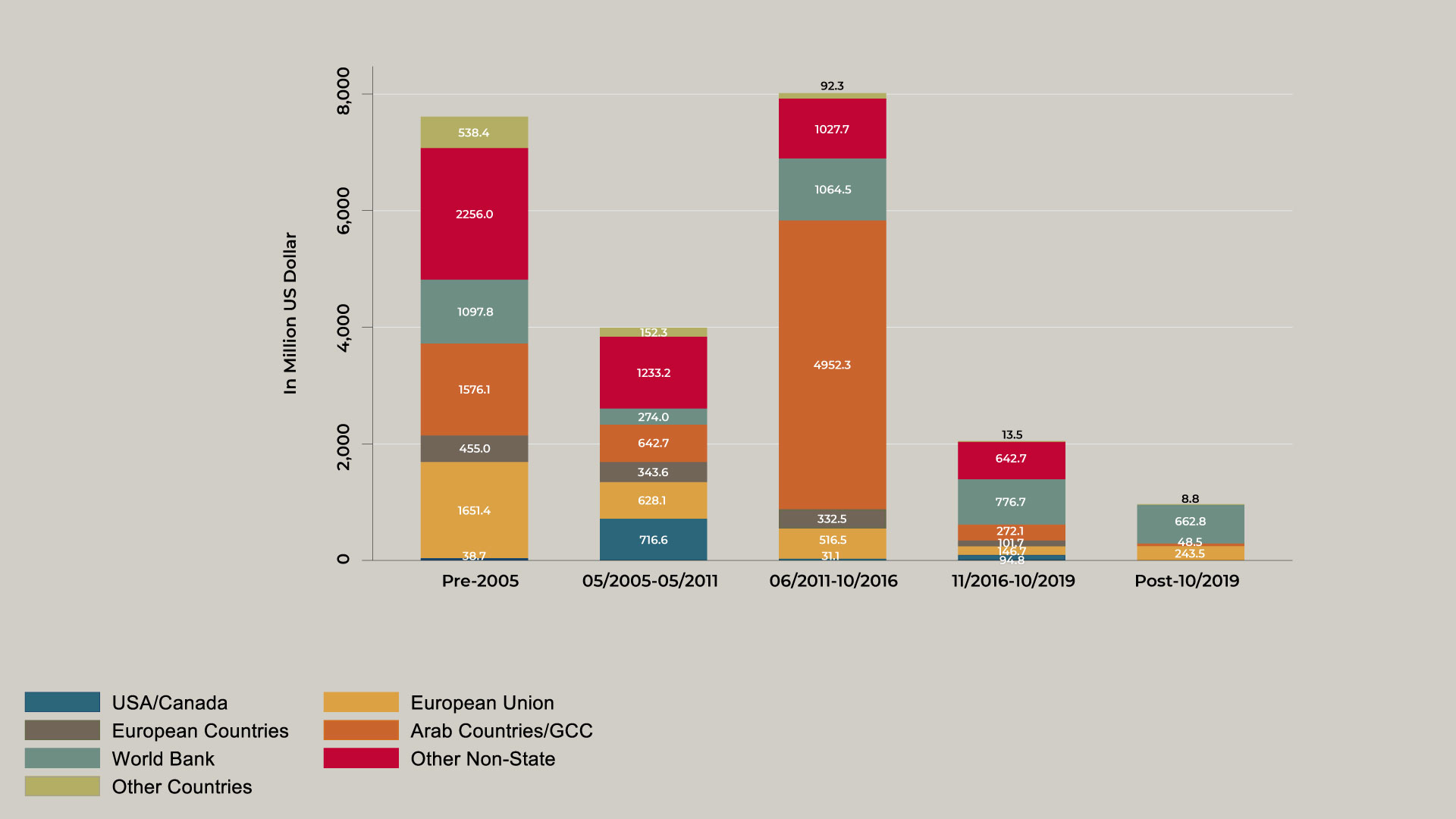

The composition of donors reflects salient political developments in Lebanon’s volatile post-war history. We identify five periods characterizing international assistance, each exhibiting a distinct composition of international donors providing grants and loans (figure 3). Three observations stand out. First, Lebanon had the most diversified set of donors in the period between February 1991 and May 2011 – reflecting widely-shared support from the international community. While the United States and Canada were only minor contributors after 1991, they increased their support in the period between 2005 and 2011.

Second, GCC countries dominated financial assistance from 2011 until the election of President Michel Aoun in October 2016. Driven by large pledges from Saudi Arabia, GCC countries provided almost 62% of all loan and grant agreements during that period (even though parts of these pledges have not been disbursed). As security issues became a priority after the outbreak of Syria’s civil war, most contributions were in the form of grants and targeted supplies to security institutions.

Third, in the period since October 2019, the diversity of donors has significantly reduced amid a paradigm shift in donor assistance. Most assistance has been driven by humanitarian projects amid worsening socio-economic conditions and increasingly targeted support in the form of in-kind contributions and support to non-governmental institutions (both of which are not reflected in our dataset), rather than providing loans or grants to state institutions. In that way, funding to state institutions declined to its lowest level in a decade, falling to $166 million in 2022 (the second-lowest annual funding since 1991). Notably, GCC countries almost entirely withdrew their financial support after the election of President Michel Aoun in 2016. After October 2019, the World Bank (68.8%) and the European Union (25.3%) remained as virtually the only institutions providing financial assistance via state institutions.

Figure 3: Composition of donor contributions over periods in time (percent of amounts pledged in grants and loans)

Financial development assistance can be an important cornerstone for exiting the present-day financial and economic crisis. However, the intransigence of Lebanon’s elites to commit to the implementation of long-overdue reforms leaves only a few donors that continue to provide financial assistance to state institutions. As donors have changed their paradigm of development assistance, encouraging a larger set of donors to reengage is likely to remain an elusive quest for governments to come.

1. The authors would like to thank Assad Thebian, founding director of Gherbal Initiative, for sharing the data with TPI as well as Najib Zoughaib and Wassim Maktabi for excellent research support and Hind Khaled for the designing the visuals.

2. Amid recent reports of mismanagement in the administration of grants of various recipient institutions, the dataset might miss some grants in the immediate post-war period. It also does not include grants and loans that have been extended to non-governmental institutions (which are not recorded in the Official Gazette) or are provided as in-kind contributions. We also do not have access to data which shows which portion of these grants and loans have been disbursed or repaid.

Related Output

view allFrom the same author

view all-

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب

More periodicals

view all-

01.15.26

ازدواجيّةُ المعايير لدى مُصنِّعي الإسمنت في لبنان: بين استخراج الموارد وحماية المشهد الطبيعيّ

منى خشنمن «الأحزمة الخضراء» إلى «المحميّات الطبيعيّة»، تعمل عمالقة صناعة الإسمنت في لبنان على تلميع صورتها البيئيّة فيما تواصل تشويه المشهد الطبيعيّ وإضرار الصحّة العامّة. إنّ إزدواجية المعايير البيئيّة لدى «الشركة الوطنيّة للإسمنت»، و«هولسيم»، و«سبلين» قد تتحوّل إلى بديل عن العدالة والمساءلة. اقرأوا مقالنا الجديد من كتابة الزميلة الأولى في مبادرة سياسات الغد د. منى خشن.

اقرأ -

12.19.25

المقالع تقضم الجبال: صناعة نظام اللاقانون

نزار صاغية, رين إبراهيمتضخّـم قطاع المقالع بعد عام 1990 بشكلٍ عشوائيّ، وتحوّل في معظمه إلى احتكارات تابعة لقوى نافذة تعمل خارج القانون. توثّـق هذه الورقة كيف تَشكّـل نظام اللاقانون في هذا القطاع، وما خلّفه من أضرار بيئيّة وماليّة واجتماعيّة، والدور الذي لعبته المواجهة القانونيّة–القضائيّة في إحداث أثر فعليّ على الأرض. ورقة بحثيّة من كتابة نزار صاغية ورين إبراهيم، ضمن مشروع “المناخ والأرض والحقّ” بالتعاون مع مبادرة سياسات الغد.

اقرأ -

11.21.25

وصفة لتبييض المسؤوليات في مجال الصرف الصحّي: الخلل في الصرف الصحي نظاميّ أيضًا

نزار صاغية, فادي إبراهيمتقدّم هذه الورقة خلاصةً دقيقة لتقرير ديوان المحاسبة الصادر في 27 شباط 2025 بشأن إدارة منظومة الصرف الصحّيّ في لبنان، مبيّنةً ما يعتريه من عموميّة وقصور، وما يكشفه ذلك من خللٍ بنيويّ في منظومة الرقابة والمحاسبة ومن الأسباب العميقة لتعثر محطّات معالجة الصرف الصحّي.

اقرأ -

04.24.25

اقتراح قانون إنشاء مناطق اقتصادية تكنولوجية: تكنولوجيا للبيع في جزر نيوليبرالية

المفكرة القانونية, مبادرة سياسات الغدتهدف هذه المسوّدة إلى تحقيق النمو الاقتصادي وخلق فرص عمل، غير أنّ تصميمها يصبّ في مصلحة قلّة من المستثمرين العاملين ضمن جيوب مغلقة، يستفيدون من إعفاءات ضريبية وكلفة أجور ومنافع أدنى للعاملين. وبالنتيجة، تُنشئ هذه الصيغة مساراً ريعيّاً فاسداً يُلحق ضرراً بإيرادات الدولة وبحقوق الموظفين وبالتخطيط الإقليمي (تجزئة المناطق). والأسوأ أنّ واضعي السياسات لا يُبدون أيّ اهتمام بتقييم أداء هذه الشركات أو مراقبته للتحقّق من تحقيق الغاية المرجوّة من المنطقة الاقتصاديّة.

اقرأ -

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

10.27.23eng

تضامناً مع العدالة وحق تقرير المصير للشعب الفلسطيني

-

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

09.09.23

بيان بشأن المادة 26 من مشروع قانون الموازنة العامة :2023

المادة ٢٦ من مشروع موازنات عام ٢٠١٣ التي اقرها مجلس الوزراء تشكل إعفاء لأصحاب الثروات الموجودة في الخارج من الضريبة النتيجة عن الأرباح والايرادات المتأتية منها تجاه الدولة اللبنانية. بينما يستمرون في الإقامة بشكل رسمي في لبنان ويتجنبون تكليفهم بالضرائب بالخارج بسبب هذه الإقامة. كما تضمنت المادة نفسها عفواً عاماً لهؤلاء من التهرب الضريبي. وكان مجلس الوزراء قد عمد إلى تعديل المادة 26 من المشروع ال مذكور، فيما كانت وزارة المالية تشددت على العكس من ذلك تماماً في تذكير بالمترتبات والنتائج القانونية والمالية الخطرة لأي تقاعس أو إخلال في تنفيذ الموجبات الضريبية ومنها الملاحقات الجزائية والحجز عىل الممتلكات و الاموال. واللافت أن هذا الإعفاء الذي يشمل ضرائب طائلة يأتي في الفترة التي الدولة هي بأمس الحاجة فيها إلى تأمين موارد تمكنها من إعادة سير مرافقها العامة ومواجهة الأزمة المالية والإقتصادية.

اقرأ -

08.24.23

من أجل تحقيق موحد ومركزي في ملف التدقيق الجنائي

في بيان مشترك مع المفكرة القانونية، مبادرة سياسات الغد، كلنا إرادة، وALDIC، نسلط الضوء على التقرير التمهيدي الذي أصدره Alvarez & Marsal حول ممارسات مصرف لبنان وأهميته كخطوة حاسمة نحو تعزيز الشفافية. ويكشف هذا التقرير عن غياب الحوكمة الرشيدة، وقضايا محاسبية، وخسائر كبيرة. إن المطلوب اليوم هو الضغط من أجل إجراء تدقيق جاد وموحد ومركزي ونشر التقرير رسمياً وبشكل كامل.

اقرأ -

07.27.23

المشكلة وقعت في التعثّر غير المنظّم تعليق دفع سندات اليوروبوندز كان صائباً 100%

-

05.17.23

حشيشة" ماكينزي للنهوض باقتصاد لبنان

-

01.12.23

وينن؟ أين اختفت شعارات المصارف؟

-

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب -

06.08.22eng

تطويق الأراضي في أعقاب أزمات لبنان المتعددة

منى خشن -

05.11.22eng

هل للانتخابات في لبنان أهمية؟

كريستيانا باريرا -

05.06.22eng

الانتخابات النيابية: المنافسة تحجب المصالح المشتركة