- عربي

-

- share

-

subscribe to our mailing listBy subscribing to our mailing list you will be kept in the know of all our projects, activities and resourcesThank you for subscribing to our mailing list.

From Hariri's Loans to Aoun's Drought

The History of Lebanon's Foreign Aid

International development assistance has been one of the fundamental pillars of Lebanon’s post-war political economy.2 Provided by various international agencies, governments, and affiliated institutions, development assistance aims to provide support where government resources are insufficient. A plethora of countries have offered billions of US dollars to the Lebanese state to support various sectors of the economy, notably for reconstruction, the improvement of infrastructure, strengthening of security institutions, and humanitarian assistance, among other aims. Such large amounts of funds, the disbursement of which are often tied to conditionalities, have had an important impact on domestic politics, the development of national institutions, as well as, inevitably, patterns of corruption and collusion.

This article is the first in a series which analyzes a new dataset of all loan and grant agreements that Lebanon’s parliaments and governments accepted after the civil war.3 This dataset, collected and generously made available by Gherbal Initiative, includes all international assistance that is recorded in the form of a law or decree and published in the Official Gazette. Amid recent reports of mismanagement in the administration of grants of various recipient institutions,4 the dataset might miss a number of grants notably in the post-war period. It does not include grants and aid that have been provided to non-governmental institutions (which are not recorded in the Official Gazette) or are provided as in-kind contributions.5 We also do not have access to data which shows which portion of these grants and loans have been disbursed or repaid. Notwithstanding, this dataset provides the first comprehensive overview of the patterns by which governments solicited – and donors offered – international assistance.

We find that the amounts and compositions of loan and grant agreements vary over distinct time periods. During the post-war period, dominated largely by Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri, development assistance consisted mostly of loan agreements. Governments after 2011, by contrast, solicited larger shares of non-repayable grants, of which the government led by Prime Minister Tammam Salam attracted the highest amounts. The composition of assistance also differed according to presidential tenures. During the tenure of President Michel Aoun, for example, Lebanon received the fewest assistance compared to all other post-war presidential tenures, even less than during periods in which the presidency was vacant. This reduction in funds exemplifies a paradigm shift of international assistance as well as changing interests and priorities in recent years by donor countries. As conditionalities for financial assistance remain unmet amid political paralysis and virtually no progress on reforms, donors shifted funding away from financial assistance to in-kind donations and direct support to non-governmental organizations.

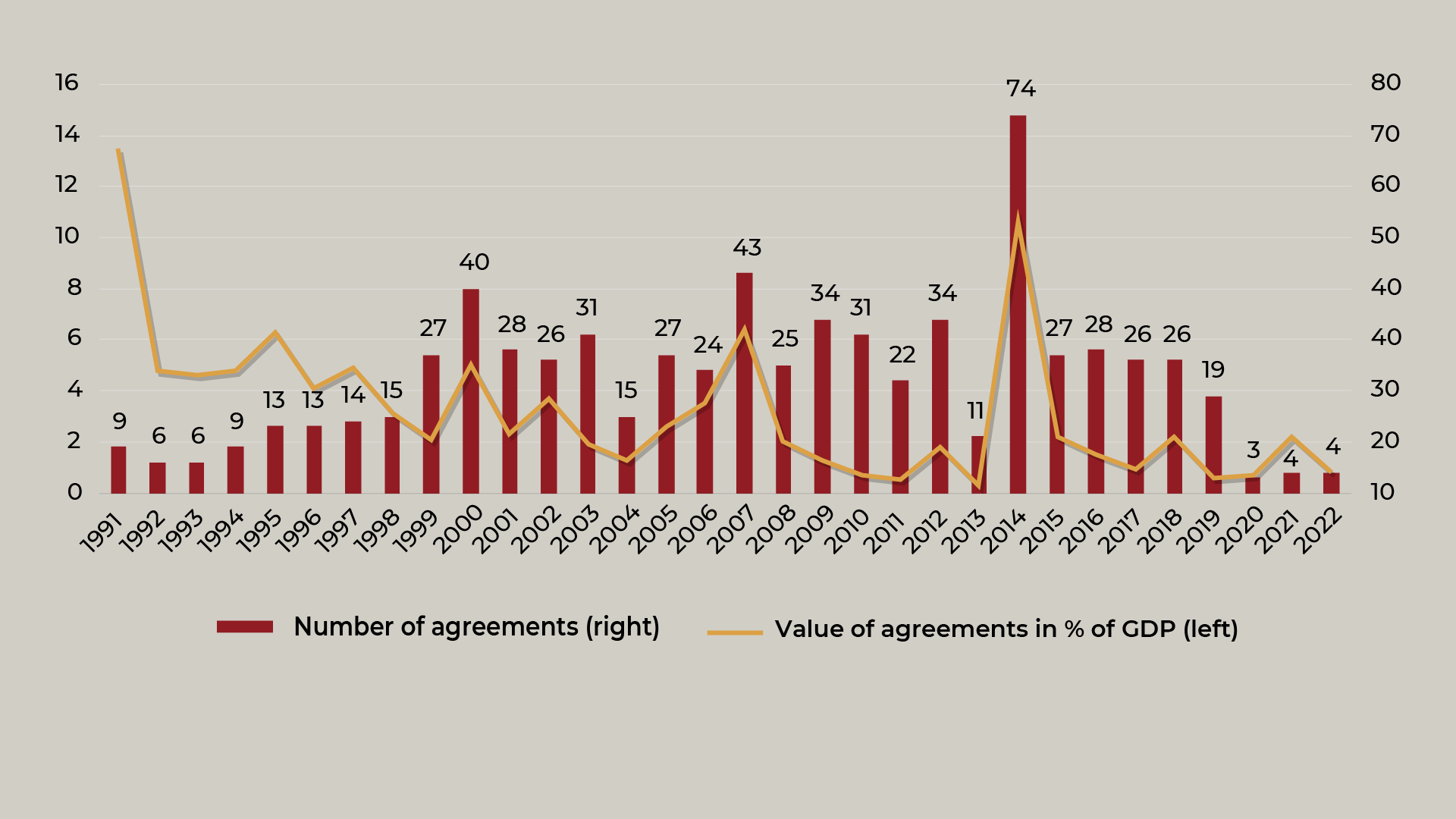

Soliciting loans and grants over 30 years

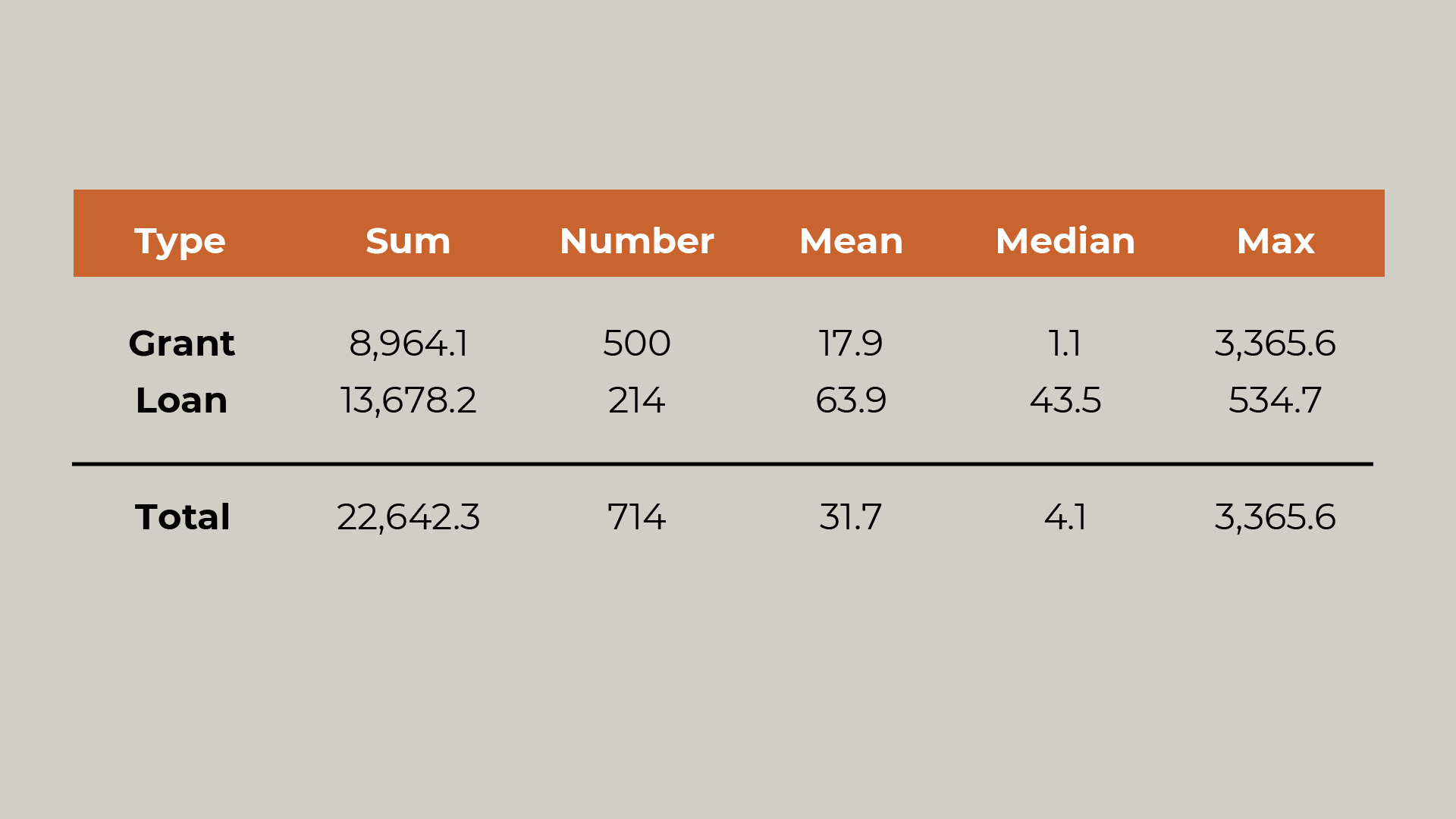

From 1991 to 2022, Lebanese governments signed 714 agreements to receive development assistance, totaling roughly $22.6 billion (inflation adjusted, in 2021 prices), 40% ($8.9 billion) of which were grants and 60% ($13.7 billion) loans. While there were less than half as many loan agreements than grants, loans were larger on average, the largest of which totaled more than $500 million. Development assistance at this scale is significant for an economy as small as Lebanon’s, representing more than 10% of GDP in 1991 and 2014, and more than 6% in 1995 and 2007.

Table 1: International development assistance from 1991 to 2022 (in millions of US Dollars, 2021 prices)

Figure 1: International development assistance in relation to national GDP (in percent) and number of agreements

Source: Lebanon Official Gazette, Gherbal Initiative, World Bank

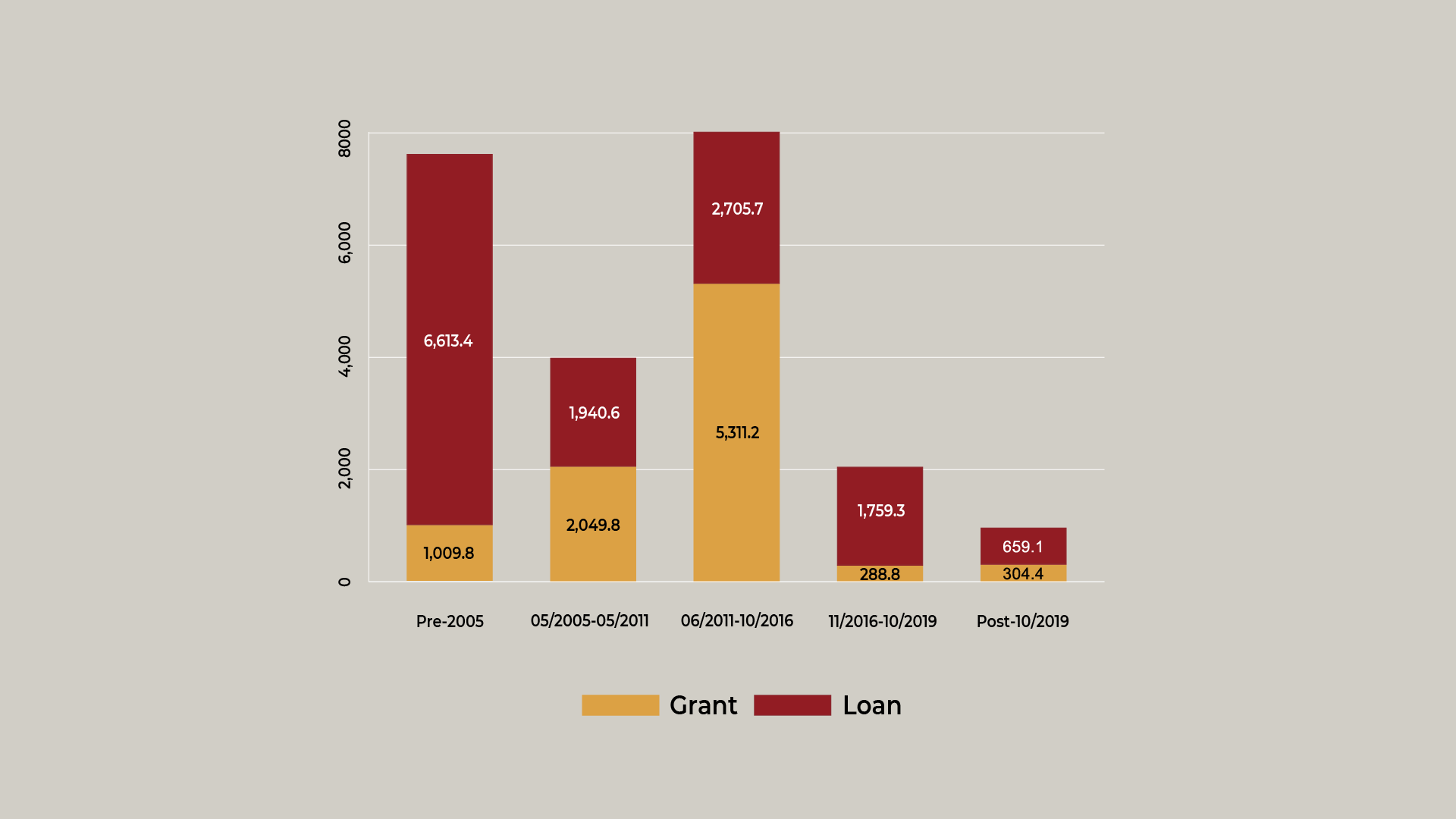

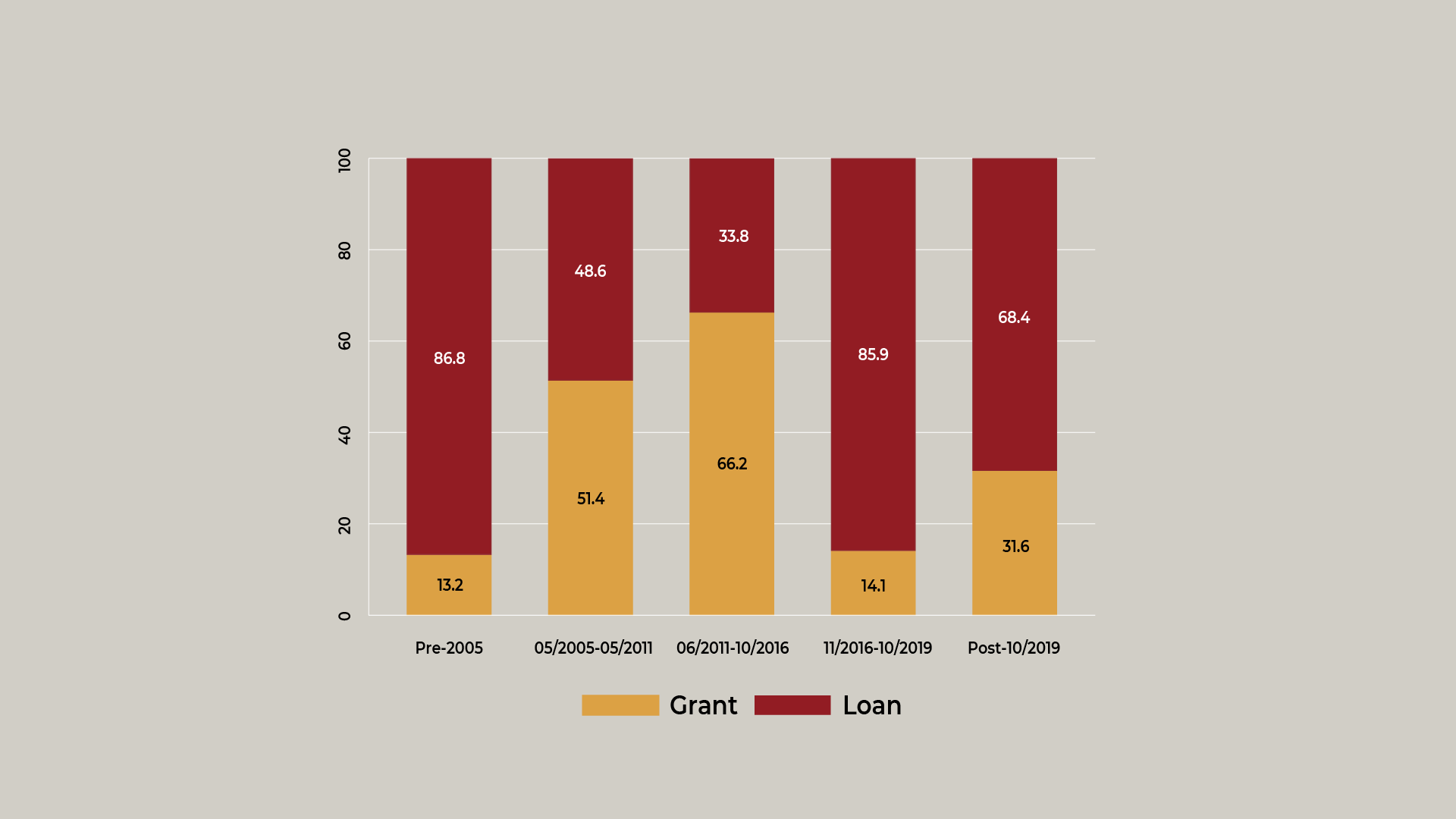

The manner in which development assistance has been granted reflects political developments throughout Lebanon’s volatile post-war history. Five distinct periods characterize international assistance. The post-war era, until the withdrawal of Syrian troops in April 2005, was marked by a heavy reliance on loans, reflecting the growth model of successive governments led by Rafiq Hariri. During that period, Lebanon solicited more than $7.6 billion in international assistance, almost 87% of which took the form of loans. Successive post-war governments increased their portfolio of agreements each year, steadily increasing the number of agreements from six in 1992 to 40 in 2000.

In the period between the assassination of Rafiq Hariri in 2005 and the outbreak of the civil war in Syria in 2011, grants became more prominent. Loan agreements totaled roughly $2 billion, matched by an equal amount in grants. Partly in response to the conflict with Israel in 2006, donors pledged various grants for reconstruction as well as for technical assistance in administrative development.

From 2011 to mid-2016, security issues and the refugee crisis became major concerns. Significant amounts of assistance to the Lebanese Armed Forces as well as support for the response to the refugee crisis increased the share of grants to more than two-thirds of all international assistance. More than $8 billion was pledged during that period, despite long periods of political paralysis.

In 2016, this pattern changed once again after a two-year presidential vacancy and Central Bank policies that brought to the fore the dire state of state finances.6 International donors became stricter in their demand for reforms as a precondition for the disbursement of assistance,7 reducing the overall amount to $2 billion. For example, conditions for the disbursement of amounts pledged during the CEDRE conference in 2018 have never been met, resulting in very few funds being disbursed. After mass-demonstrations and the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2019, donors reduced financial commitments to state institutions to less than $1 billion. As the number of agreements dropped from 74 in 2014 to only three in 2020, assistance instead shifted to humanitarian operations to address the fallout of the crisis, such as the World Bank’s cash-transfer program. Donor programs became “people-centered” and increasingly aimed at providing targeted support in the form of in-kind contributions or direct support to non-governmental institutions. Notably, despite the government defaulting on its sovereign debt in 2020 and the significant fiduciary risks related to the treasury’s ability to repay, donors continued to grant loans for various pressing issues, which totaled more than $650 million from October 2019 to the end of 2022.8

Figure 2: Amount (in millions of US dollars) and share of loans and grants in periods

Between the loans of Hariri and the grants of Salam

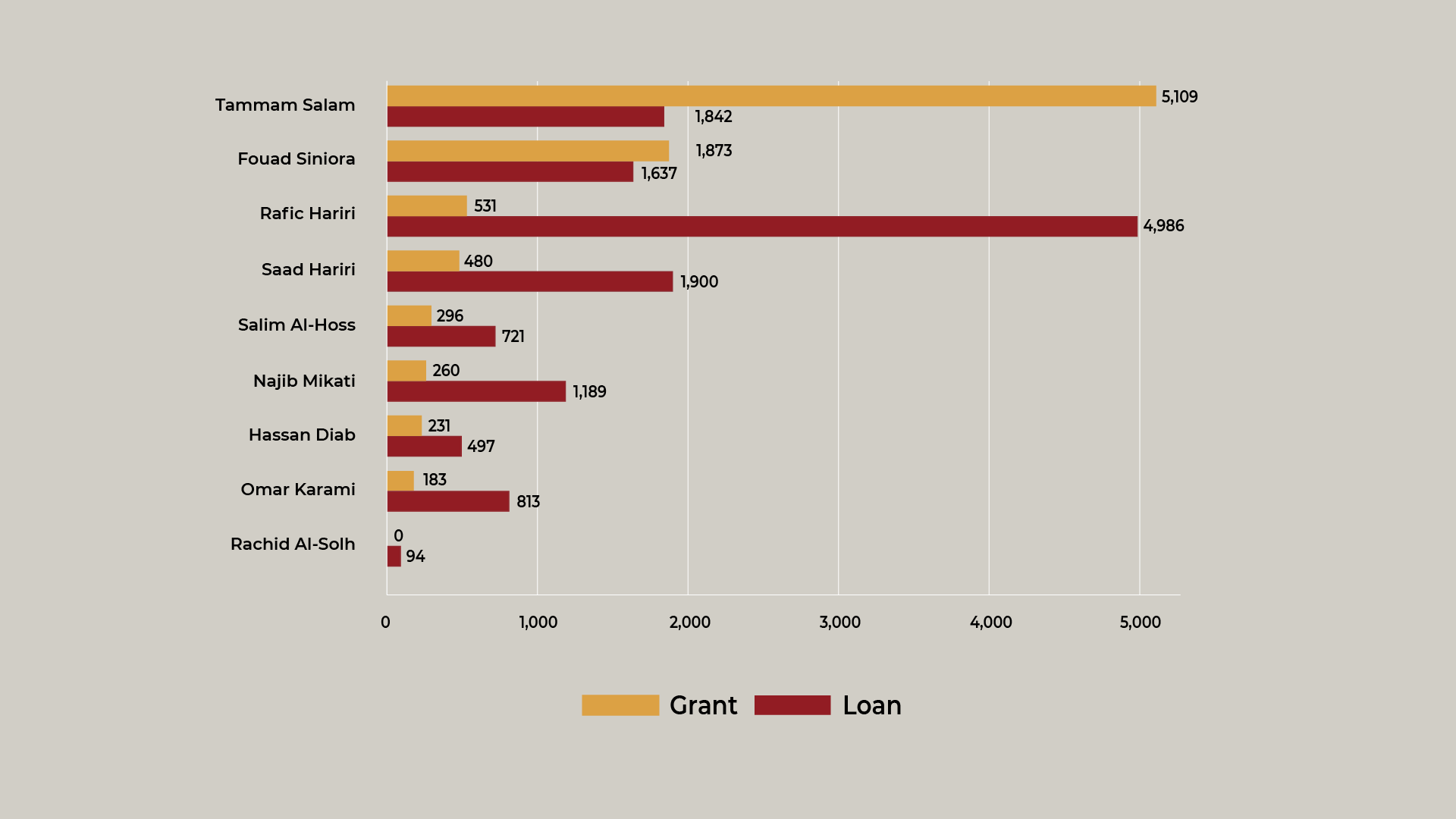

The persona of prime ministers is widely perceived as being an important determinant in attracting assistance. They or their governments’ agendas can be more or less aligned with the priorities of international donors, or prime ministers can leverage personal connections to solicit grants and loans. Indeed, Lebanon’s prime ministers and presidents have a mixed record of soliciting grants and loans. While Salam’s government attracted the most grants – to the tune of more than $5.1 billion – Rafiq Hariri’s governments accepted the largest amount of loans, totaling nearly $5 billion.

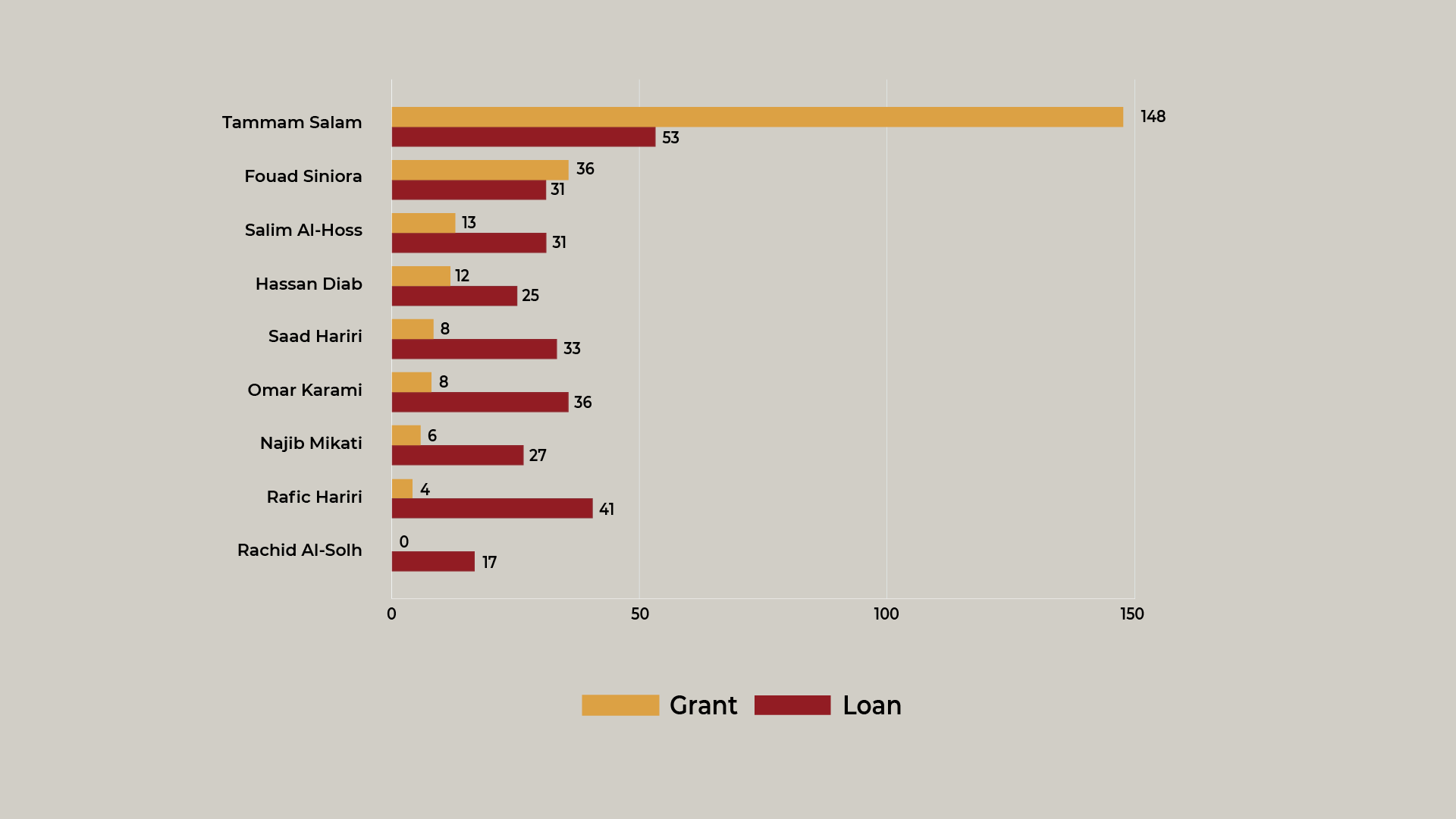

Normalizing these amounts by the months a prime minister stayed in office, however, shows that prime ministers differ more in terms of their ability to solicit grants, rather than loans. Salam outranks all other prime ministers by having solicited $148 million in grants per month in office, more than four times as much as the second-placed Prime Minister Fouad Siniora. In term of loans, however, differences between prime ministers are much smaller. Apart from the government under Prime Minister Rachid Al-Solh after the civil war, all prime ministers closed loan agreements valued at $25 million to $40 million per month in office.

Figure 3: Grants and loans by prime minister, in total and normalized by months in office in millions of US dollars

Aid with or without a president

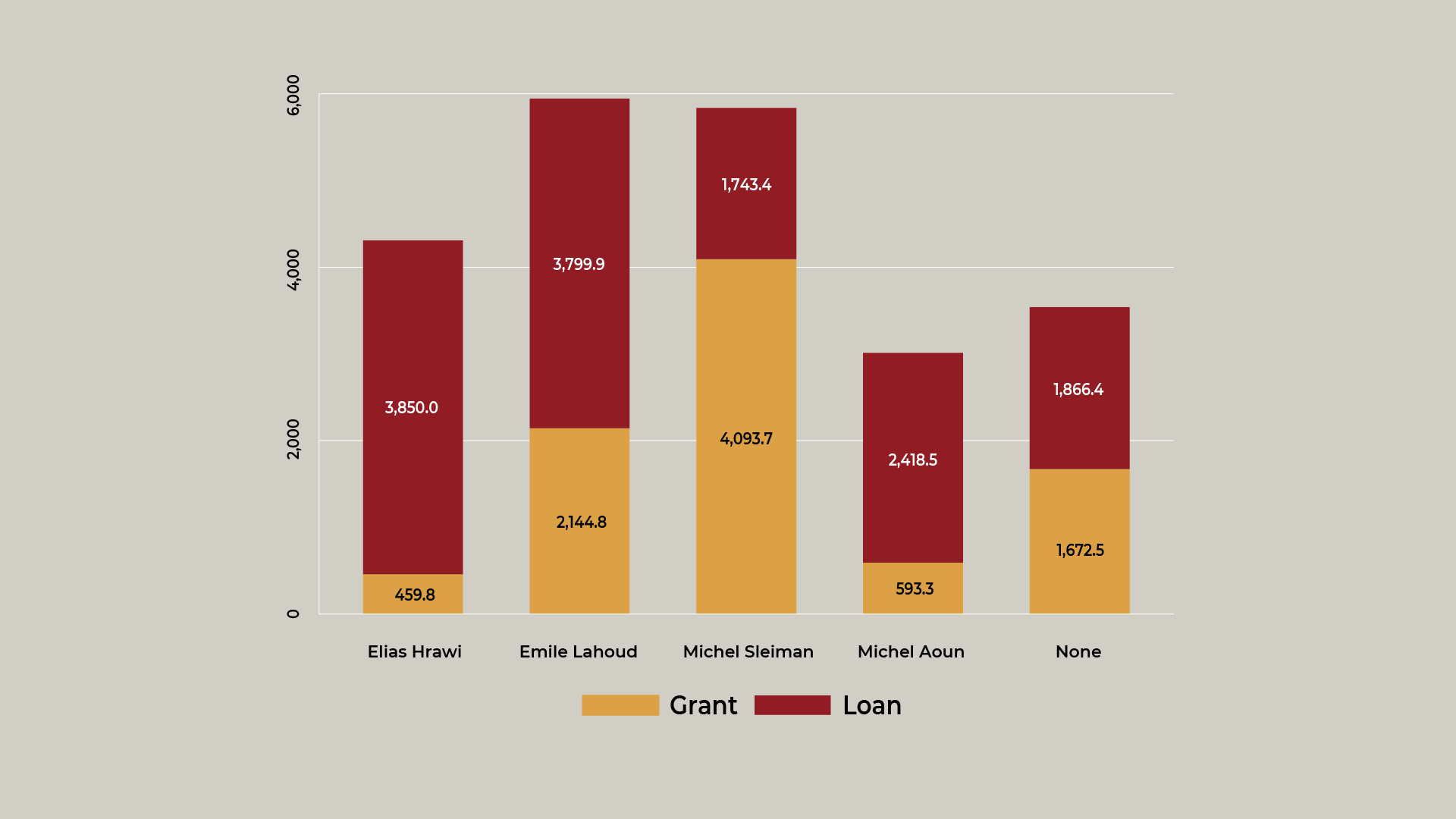

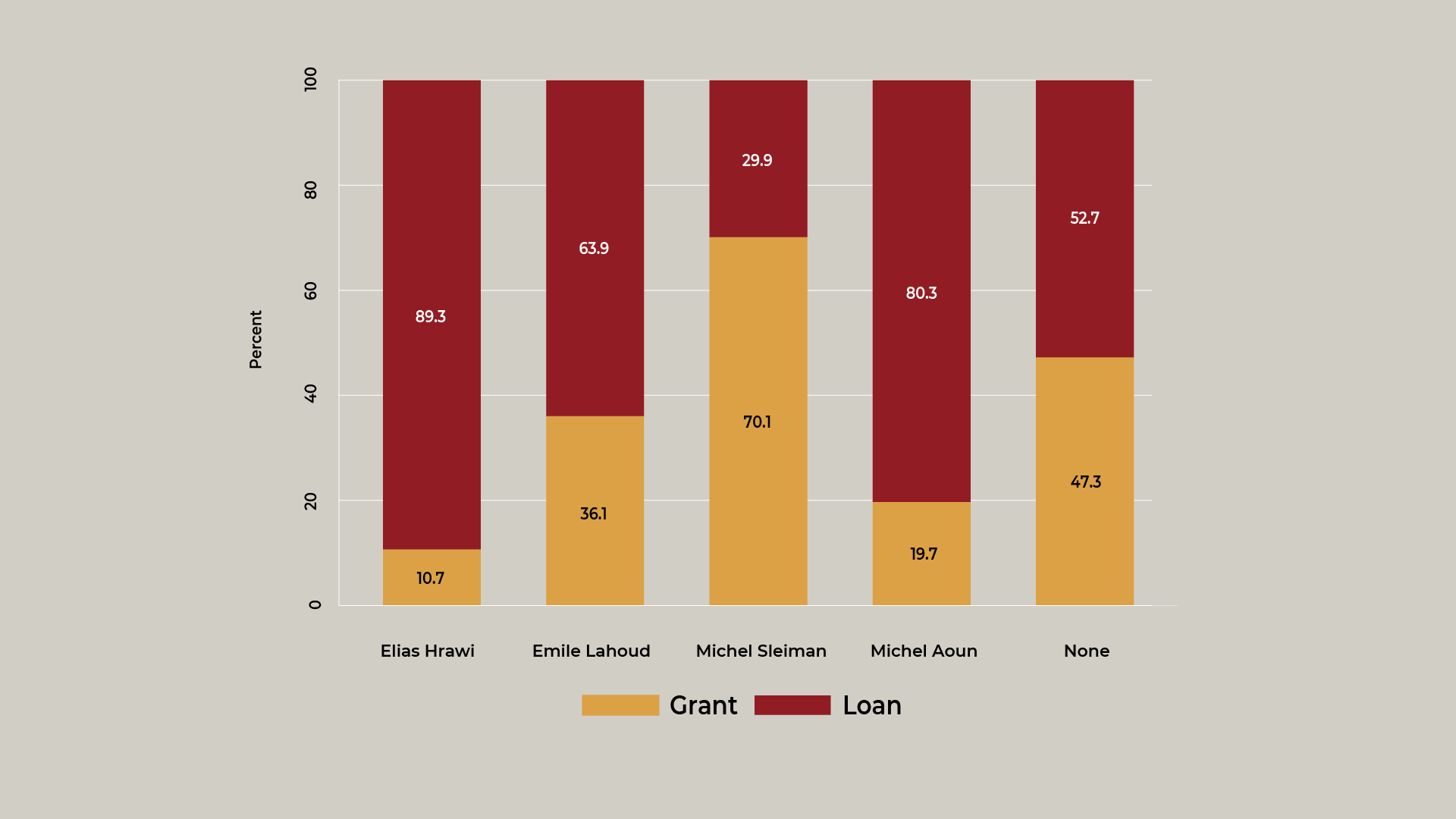

While a prime minister outlines the program of a government, presidents are also involved in shaping strategic priorities, notably with respect to international relations. Under President Michel Sleiman (2008-2014), Lebanon’s governments solicited more than $4 billion in grants, more than during all other presidential periods. During the tenure of President Elias Hrawi (1989-1998) and President Emile Lahoud (1998-2007), governments signed the most loan agreements in the post-war era. Governments during the tenure of President Michel Aoun (2016-2022), however, solicited the least international assistance and notably only a few grants. Accordingly, the share of loans to grants was more than 80%, almost as high as during the tenure of Hrawi after the civil war (almost 90%). Even though caretaker governments have limited authority to implement conditionalities for reform, they signed agreements totaling more than $3.5 billion.

Figure 4: Amount (in millions of US dollars) and share of grants and loan agreements during presidential tenures

Given the importance of international development assistance to Lebanon’s political economy, incoming loans and grants mirror Lebanon’s volatile post-civil war history. Today, in the context of cascading crises, international assistance would be more important than ever to provide resources – which Lebanon’s governments will lack for years to come – to invest in dilapidated infrastructure, human development and humanitarian assistance, or institutional capacities, among so many other areas of concern. Amid prolonged political paralysis and concerns over corruption and mishandling of funds, Lebanon’s politicians will likely be unable or unwilling to deliver on the conditions for the disbursement of assistance necessary to address the egregious fallout of the present-day crises.8

1. The authors would like to thank Assad Thebian, founding director of Gherbal Initiative, for sharing the data with TPI as well as Najib Zoughaib and Wassim Maktabi for excellent research support.

2. Leenders, R., Spoils of Truce: Corruption and State-Building in Postwar Lebanon, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012; Makdisi, S., The Lessons of Lebanon - The Economics of War, London: I.B. Tauris, 2004; Zahar, M.-J., Power Sharing in Lebanon: Foreign Protectors, Domestic Peace, and Democratic Failure, in Sustainable Peace: Power and Democracy After Civil Wars, P. G. Roeder and D. Rothchild, Eds., Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, pp. 219–40, 2005.

3. Most loan and grant agreements with international institutions and foreign governments need to be accepted in the form of laws. As parliament accepts these laws, they are published in Lebanon’s Official Gazette, the governmental journal all legislation has to be published in to take effect and become legally binding. Based on these laws and decrees, we observe the details of the funding agreement, the funding agency, the grantee, the amount, the sector, and other details.

4. LBCI (2023) “Lebanon's mismanagement of internal and external grants since 1993”, Available at: https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/news-bulletin-reports/690774/lebanons-mismanagement-of-internal-and-external-gr/en

5. We exclude in-kind donations from this view, as these take various forms and often cannot be attributed to an exact monetary value.

6. World Bank (2016) “Lebanon Economic Monitor – The great swap” The World Bank, Washington DC.

7. Deutsche Welle (2020) “Beirut Blast: Donors want reforms in return for aid”.

8. Note that our dataset includes all laws and decrees that have been published in the Official Gazette until the end of 2022. Since some legislation is published with delay after their contractual agreements, our dataset might miss out on agreements that were signed towards the end of 2022 but were not yet published or published in 2023 only.

From the same author

view all-

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب

More periodicals

view all-

01.15.26

ازدواجيّةُ المعايير لدى مُصنِّعي الإسمنت في لبنان: بين استخراج الموارد وحماية المشهد الطبيعيّ

منى خشنمن «الأحزمة الخضراء» إلى «المحميّات الطبيعيّة»، تعمل عمالقة صناعة الإسمنت في لبنان على تلميع صورتها البيئيّة فيما تواصل تشويه المشهد الطبيعيّ وإضرار الصحّة العامّة. إنّ إزدواجية المعايير البيئيّة لدى «الشركة الوطنيّة للإسمنت»، و«هولسيم»، و«سبلين» قد تتحوّل إلى بديل عن العدالة والمساءلة. اقرأوا مقالنا الجديد من كتابة الزميلة الأولى في مبادرة سياسات الغد د. منى خشن.

اقرأ -

12.19.25

المقالع تقضم الجبال: صناعة نظام اللاقانون

نزار صاغية, رين إبراهيمتضخّـم قطاع المقالع بعد عام 1990 بشكلٍ عشوائيّ، وتحوّل في معظمه إلى احتكارات تابعة لقوى نافذة تعمل خارج القانون. توثّـق هذه الورقة كيف تَشكّـل نظام اللاقانون في هذا القطاع، وما خلّفه من أضرار بيئيّة وماليّة واجتماعيّة، والدور الذي لعبته المواجهة القانونيّة–القضائيّة في إحداث أثر فعليّ على الأرض. ورقة بحثيّة من كتابة نزار صاغية ورين إبراهيم، ضمن مشروع “المناخ والأرض والحقّ” بالتعاون مع مبادرة سياسات الغد.

اقرأ -

11.21.25

وصفة لتبييض المسؤوليات في مجال الصرف الصحّي: الخلل في الصرف الصحي نظاميّ أيضًا

نزار صاغية, فادي إبراهيمتقدّم هذه الورقة خلاصةً دقيقة لتقرير ديوان المحاسبة الصادر في 27 شباط 2025 بشأن إدارة منظومة الصرف الصحّيّ في لبنان، مبيّنةً ما يعتريه من عموميّة وقصور، وما يكشفه ذلك من خللٍ بنيويّ في منظومة الرقابة والمحاسبة ومن الأسباب العميقة لتعثر محطّات معالجة الصرف الصحّي.

اقرأ -

04.24.25

اقتراح قانون إنشاء مناطق اقتصادية تكنولوجية: تكنولوجيا للبيع في جزر نيوليبرالية

المفكرة القانونية, مبادرة سياسات الغدتهدف هذه المسوّدة إلى تحقيق النمو الاقتصادي وخلق فرص عمل، غير أنّ تصميمها يصبّ في مصلحة قلّة من المستثمرين العاملين ضمن جيوب مغلقة، يستفيدون من إعفاءات ضريبية وكلفة أجور ومنافع أدنى للعاملين. وبالنتيجة، تُنشئ هذه الصيغة مساراً ريعيّاً فاسداً يُلحق ضرراً بإيرادات الدولة وبحقوق الموظفين وبالتخطيط الإقليمي (تجزئة المناطق). والأسوأ أنّ واضعي السياسات لا يُبدون أيّ اهتمام بتقييم أداء هذه الشركات أو مراقبته للتحقّق من تحقيق الغاية المرجوّة من المنطقة الاقتصاديّة.

اقرأ -

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

10.27.23eng

تضامناً مع العدالة وحق تقرير المصير للشعب الفلسطيني

-

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

09.09.23

بيان بشأن المادة 26 من مشروع قانون الموازنة العامة :2023

المادة ٢٦ من مشروع موازنات عام ٢٠١٣ التي اقرها مجلس الوزراء تشكل إعفاء لأصحاب الثروات الموجودة في الخارج من الضريبة النتيجة عن الأرباح والايرادات المتأتية منها تجاه الدولة اللبنانية. بينما يستمرون في الإقامة بشكل رسمي في لبنان ويتجنبون تكليفهم بالضرائب بالخارج بسبب هذه الإقامة. كما تضمنت المادة نفسها عفواً عاماً لهؤلاء من التهرب الضريبي. وكان مجلس الوزراء قد عمد إلى تعديل المادة 26 من المشروع ال مذكور، فيما كانت وزارة المالية تشددت على العكس من ذلك تماماً في تذكير بالمترتبات والنتائج القانونية والمالية الخطرة لأي تقاعس أو إخلال في تنفيذ الموجبات الضريبية ومنها الملاحقات الجزائية والحجز عىل الممتلكات و الاموال. واللافت أن هذا الإعفاء الذي يشمل ضرائب طائلة يأتي في الفترة التي الدولة هي بأمس الحاجة فيها إلى تأمين موارد تمكنها من إعادة سير مرافقها العامة ومواجهة الأزمة المالية والإقتصادية.

اقرأ -

08.24.23

من أجل تحقيق موحد ومركزي في ملف التدقيق الجنائي

في بيان مشترك مع المفكرة القانونية، مبادرة سياسات الغد، كلنا إرادة، وALDIC، نسلط الضوء على التقرير التمهيدي الذي أصدره Alvarez & Marsal حول ممارسات مصرف لبنان وأهميته كخطوة حاسمة نحو تعزيز الشفافية. ويكشف هذا التقرير عن غياب الحوكمة الرشيدة، وقضايا محاسبية، وخسائر كبيرة. إن المطلوب اليوم هو الضغط من أجل إجراء تدقيق جاد وموحد ومركزي ونشر التقرير رسمياً وبشكل كامل.

اقرأ -

07.27.23

المشكلة وقعت في التعثّر غير المنظّم تعليق دفع سندات اليوروبوندز كان صائباً 100%

-

05.17.23

حشيشة" ماكينزي للنهوض باقتصاد لبنان

-

01.12.23

وينن؟ أين اختفت شعارات المصارف؟

-

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب -

06.08.22eng

تطويق الأراضي في أعقاب أزمات لبنان المتعددة

منى خشن -

05.11.22eng

هل للانتخابات في لبنان أهمية؟

كريستيانا باريرا -

05.06.22eng

الانتخابات النيابية: المنافسة تحجب المصالح المشتركة