- عربي

-

- share

-

subscribe to our mailing listBy subscribing to our mailing list you will be kept in the know of all our projects, activities and resourcesThank you for subscribing to our mailing list.

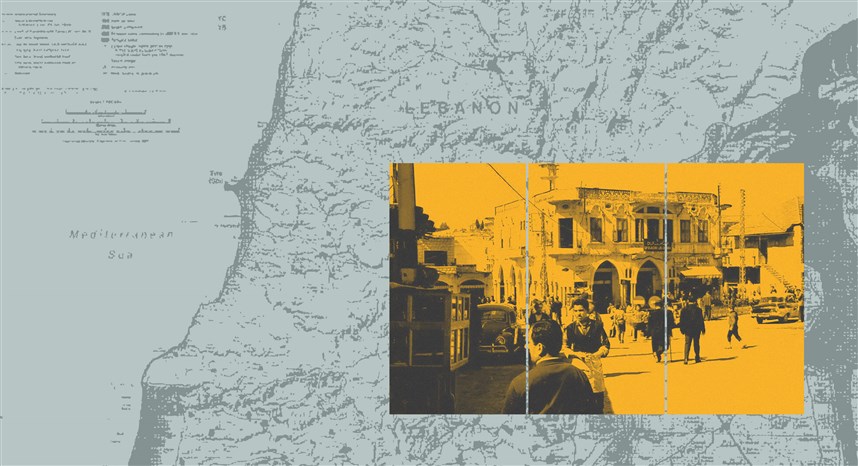

Rebuilding South Lebanon without Public Funds or Foreign Loans

South Lebanon, a region rich in natural resources, culture, and human potential, has long suffered from chronic underdevelopment due to political instability, security concerns, and limited investment. In the wake of recent destruction and ongoing economic collapse, it faces a monumental challenge: rebuilding infrastructure, stimulating private sector activity, reviving the economy, and fostering long-term resilience. Traditionally, such efforts have relied on foreign loans, donor aid, or the national budget. Yet with the Lebanese state fiscally bankrupt and foreign assistance uncertain or politically constrained, the government must turn to creative, non-monetary methods to encourage private investment. A bold, innovative, and self-reliant approach can allow the state to contribute meaningfully to recovery without tapping public funds or incurring new debt.

Encouragingly, incentives are not always financial. Governments worldwide have spurred growth through legal reform, regulatory improvement, land use, and strategic partnerships. This article outlines a roadmap for how the Lebanese government can act as facilitator, regulator, and enabler to rebuild and restart South Lebanon’s economy—using existing assets, underutilized laws, and sound policy frameworks.

1. Land and Real Estate as Development Tools

Unlocking the value of land and real estate is essential. The South holds extensive underused properties, including state-owned and abandoned sites. Instead of politically sensitive sales, the government can offer 25–50-year leases for agriculture, logistics, factories, or tourism. It can also designate industrial, agro-processing, and eco-tourism zones while guaranteeing investors’ rights through transparent contracts. Religious and charitable endowments (waqf) hold further untapped assets. Legal frameworks could allow mosques or churches to lease land for social enterprises or housing, or to enter joint ventures in education, health, and housing. Such measures transform land into non-monetary capital, stimulating construction, jobs, and economic activity.

2. Smart Tax and Customs Incentives

While Lebanon cannot afford subsidies, it can use targeted tax measures that cost little upfront yet generate long-term revenue. These include ten-year tax holidays for companies investing in job creation, and customs exemptions for equipment—machinery, solar panels, irrigation systems—used in the South. Such incentives reduce startup costs and make the region more attractive without direct cash outlays.

3. Policy and Regulatory Reform

Policy reform is vital to attract private capital. One of government’s most powerful tools is simplicity. Starting or expanding a business in Lebanon is notoriously bureaucratic. A “One-Stop Shop” for South Lebanon—digital or physical—could centralize permits, licensing, tax registration, and land approvals. Priority sectors like construction, agriculture, food processing, renewable energy, and tourism could receive fast-track licensing. Clear timelines for permits, swift contract enforcement, and specialized courts for disputes would further reduce uncertainty.

4. Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Innovation and entrepreneurship can be supported without new spending. Vacant public or municipal buildings could be converted into incubators or shared production spaces. Partnerships with universities could expand training, microfinance access, and mentorship in food processing, renewable energy, and agritech. A registry of local suppliers and services could help new businesses connect with partners and build domestic value chains.

5. Leveraging the Diaspora

South Lebanon’s diaspora offers financial capital, skills, and global networks. Rather than soliciting charity, the government could establish a South Lebanon Diaspora Investment Fund, independently governed but policy-backed, to pool capital for profit-driven ventures like solar farms, greenhouses, tourism, or digital infrastructure. “Reconstruction bonds” targeting diaspora investors could offer tax-free returns tied to projects in the South. Skills-return programs could connect diaspora engineers, doctors, and tech experts with local institutions through remote collaboration or short-term fellowships. These measures attract foreign exchange, mobilize private capital, and link the region to global markets.

6. Cooperative Models for Local Economies

Local economies can be revitalized through cooperative models. Instead of relying on state-run services or aid, the government could enable agriculture, crafts, and small industries through cooperatives. Support could include reduced registration fees, standard governance templates, and linkages with banks and buyers. A “Southern Cooperative Alliance” could serve as an umbrella body, assisting co-ops in dairy, olive oil, citrus, and handicrafts with training, bulk purchasing, and e-commerce platforms. Co-ops could also be allowed to operate on public lands with clear leases, regenerating employment in depopulated or war-damaged areas.

7. Tourism and Cultural Assets

South Lebanon’s natural and cultural resources can be monetized. Its mountains, rivers, and archaeological sites hold enormous potential for eco-tourism and cultural industries. The government could grant vetted entrepreneurs or cooperatives concessions to manage heritage sites or eco-parks in exchange for maintenance and job guarantees. A “South Lebanon Tourism Accelerator” could support entrepreneurs with business planning, branding, and digital marketing. Promoting agritourism—linking farmers, guesthouses, and local cuisine—could further boost rural income and reshape the region’s global image.

Conclusion

Lebanon’s constraints are severe, but they cannot justify paralysis. By shifting from spender to enabler, the government can spark reconstruction and revival in South Lebanon. Through land reform, cooperative empowerment, diaspora engagement, and smart regulation, it can attract capital, mobilize communities, and restore dignity—without spending public money or taking on debt.

South Lebanon’s recovery can serve as a model for the rest of Lebanon and for other post-conflict regions striving for self-reliance and sustainable development. What is required for South Lebanon’s reconstruction is not new borrowing, but right policy mix and political will to act as facilitator, regulator, and guarantor. By removing barriers, offering land, legal clarity, and tax relief, and mobilizing local and diaspora talent, the Lebanese government can transform South Lebanon from a zone of crisis into a laboratory for innovative, community-driven growth—demonstrating that recovery without public funds is not only possible, but sustainable.

From the same author

view allMore periodicals

view all-

01.15.26

ازدواجيّةُ المعايير لدى مُصنِّعي الإسمنت في لبنان: بين استخراج الموارد وحماية المشهد الطبيعيّ

منى خشنمن «الأحزمة الخضراء» إلى «المحميّات الطبيعيّة»، تعمل عمالقة صناعة الإسمنت في لبنان على تلميع صورتها البيئيّة فيما تواصل تشويه المشهد الطبيعيّ وإضرار الصحّة العامّة. إنّ إزدواجية المعايير البيئيّة لدى «الشركة الوطنيّة للإسمنت»، و«هولسيم»، و«سبلين» قد تتحوّل إلى بديل عن العدالة والمساءلة. اقرأوا مقالنا الجديد من كتابة الزميلة الأولى في مبادرة سياسات الغد د. منى خشن.

اقرأ -

12.19.25

المقالع تقضم الجبال: صناعة نظام اللاقانون

نزار صاغية, رين إبراهيمتضخّـم قطاع المقالع بعد عام 1990 بشكلٍ عشوائيّ، وتحوّل في معظمه إلى احتكارات تابعة لقوى نافذة تعمل خارج القانون. توثّـق هذه الورقة كيف تَشكّـل نظام اللاقانون في هذا القطاع، وما خلّفه من أضرار بيئيّة وماليّة واجتماعيّة، والدور الذي لعبته المواجهة القانونيّة–القضائيّة في إحداث أثر فعليّ على الأرض. ورقة بحثيّة من كتابة نزار صاغية ورين إبراهيم، ضمن مشروع “المناخ والأرض والحقّ” بالتعاون مع مبادرة سياسات الغد.

اقرأ -

11.21.25

وصفة لتبييض المسؤوليات في مجال الصرف الصحّي: الخلل في الصرف الصحي نظاميّ أيضًا

نزار صاغية, فادي إبراهيمتقدّم هذه الورقة خلاصةً دقيقة لتقرير ديوان المحاسبة الصادر في 27 شباط 2025 بشأن إدارة منظومة الصرف الصحّيّ في لبنان، مبيّنةً ما يعتريه من عموميّة وقصور، وما يكشفه ذلك من خللٍ بنيويّ في منظومة الرقابة والمحاسبة ومن الأسباب العميقة لتعثر محطّات معالجة الصرف الصحّي.

اقرأ -

04.24.25

اقتراح قانون إنشاء مناطق اقتصادية تكنولوجية: تكنولوجيا للبيع في جزر نيوليبرالية

المفكرة القانونية, مبادرة سياسات الغدتهدف هذه المسوّدة إلى تحقيق النمو الاقتصادي وخلق فرص عمل، غير أنّ تصميمها يصبّ في مصلحة قلّة من المستثمرين العاملين ضمن جيوب مغلقة، يستفيدون من إعفاءات ضريبية وكلفة أجور ومنافع أدنى للعاملين. وبالنتيجة، تُنشئ هذه الصيغة مساراً ريعيّاً فاسداً يُلحق ضرراً بإيرادات الدولة وبحقوق الموظفين وبالتخطيط الإقليمي (تجزئة المناطق). والأسوأ أنّ واضعي السياسات لا يُبدون أيّ اهتمام بتقييم أداء هذه الشركات أو مراقبته للتحقّق من تحقيق الغاية المرجوّة من المنطقة الاقتصاديّة.

اقرأ -

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

10.27.23eng

تضامناً مع العدالة وحق تقرير المصير للشعب الفلسطيني

-

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

09.09.23

بيان بشأن المادة 26 من مشروع قانون الموازنة العامة :2023

المادة ٢٦ من مشروع موازنات عام ٢٠١٣ التي اقرها مجلس الوزراء تشكل إعفاء لأصحاب الثروات الموجودة في الخارج من الضريبة النتيجة عن الأرباح والايرادات المتأتية منها تجاه الدولة اللبنانية. بينما يستمرون في الإقامة بشكل رسمي في لبنان ويتجنبون تكليفهم بالضرائب بالخارج بسبب هذه الإقامة. كما تضمنت المادة نفسها عفواً عاماً لهؤلاء من التهرب الضريبي. وكان مجلس الوزراء قد عمد إلى تعديل المادة 26 من المشروع ال مذكور، فيما كانت وزارة المالية تشددت على العكس من ذلك تماماً في تذكير بالمترتبات والنتائج القانونية والمالية الخطرة لأي تقاعس أو إخلال في تنفيذ الموجبات الضريبية ومنها الملاحقات الجزائية والحجز عىل الممتلكات و الاموال. واللافت أن هذا الإعفاء الذي يشمل ضرائب طائلة يأتي في الفترة التي الدولة هي بأمس الحاجة فيها إلى تأمين موارد تمكنها من إعادة سير مرافقها العامة ومواجهة الأزمة المالية والإقتصادية.

اقرأ -

08.24.23

من أجل تحقيق موحد ومركزي في ملف التدقيق الجنائي

في بيان مشترك مع المفكرة القانونية، مبادرة سياسات الغد، كلنا إرادة، وALDIC، نسلط الضوء على التقرير التمهيدي الذي أصدره Alvarez & Marsal حول ممارسات مصرف لبنان وأهميته كخطوة حاسمة نحو تعزيز الشفافية. ويكشف هذا التقرير عن غياب الحوكمة الرشيدة، وقضايا محاسبية، وخسائر كبيرة. إن المطلوب اليوم هو الضغط من أجل إجراء تدقيق جاد وموحد ومركزي ونشر التقرير رسمياً وبشكل كامل.

اقرأ -

07.27.23

المشكلة وقعت في التعثّر غير المنظّم تعليق دفع سندات اليوروبوندز كان صائباً 100%

-

05.17.23

حشيشة" ماكينزي للنهوض باقتصاد لبنان

-

01.12.23

وينن؟ أين اختفت شعارات المصارف؟

-

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب -

06.08.22eng

تطويق الأراضي في أعقاب أزمات لبنان المتعددة

منى خشن -

05.11.22eng

هل للانتخابات في لبنان أهمية؟

كريستيانا باريرا -

05.06.22eng

الانتخابات النيابية: المنافسة تحجب المصالح المشتركة