- عربي

-

- share

-

subscribe to our mailing listBy subscribing to our mailing list you will be kept in the know of all our projects, activities and resourcesThank you for subscribing to our mailing list.

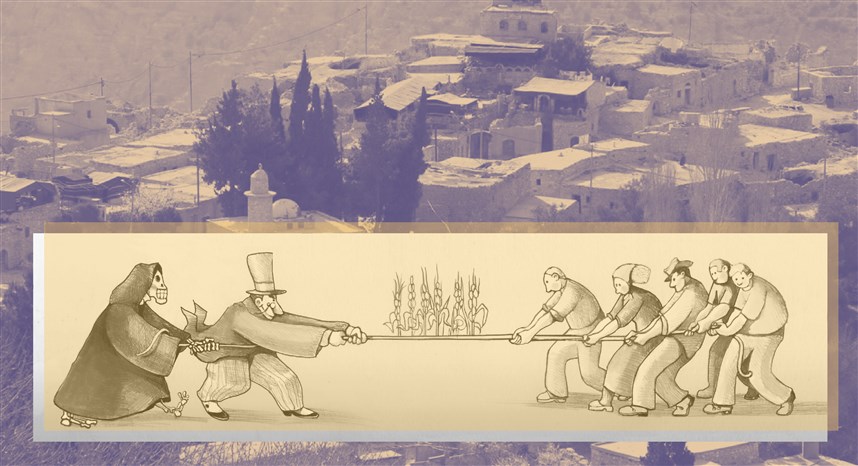

How Land Grabbing in the Arab World Threatens Our Shared Future

One morning in Dana village, on the outskirts of Jordan’s southern highlands, pastoralist families discovered a newly erected fence cutting through their grazing lands. Without warning, the area had been designated a government-protected nature reserve. While authorities framed the project as a step toward environmental sustainability, the families - who had relied on that land for generations - were neither informed nor consulted. Meanwhile, in a High Atlas village in Morocco, Amazigh pastoralist families awoke to find their ancestral grazing lands reclassified overnight as state-managed reforested zones, as part of a forestry-led conservation initiative. Though officials heralded the project as an environmental victory, the communities who had herded these lands for generations were neither consulted nor compensated. Customary governance structures were bypassed, and traditional land claims were overridden. These scenes have become emblematic of a broader pattern across the Arab world, where development projects promoted under the guise of sustainability and climate action are quietly dispossessing local communities. Behind the promise of green transformation lies a growing crisis: the silent appropriation of land and natural resources under the banner of environmental progress.

This article examines the growing phenomenon of "green grabbing" in the Arab region – the acquisition or privatization of land, in the name of conservation, renewable energy, or sustainability. Although such projects often claim alignment with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), their real-world effects frequently undermine those very aims. Instead of promoting poverty reduction, equality, and environmental health, green grabbing tends to deepen marginalization, disrupt livelihoods, and even endanger the ecosystem it purports to protect. This article argues that unless justice and rights are woven into sustainability efforts, the Arab region risks merely exchanging one form of inequality for another.

The Arab world faces a convergence of structural challenges: worsening land scarcity, intensifying water stress, mounting climate vulnerability, and deep-rooted socio-economic inequality. In this context, green investments such as solar farms, reforestation projects, and conservation zones are often embraced as solutions. Yet, these initiatives can obscure a deeper problem - exclusion. Far from being neutral, they reshape land relations, concentrate resources in the hands of elites, and displace communities that have long used and cared for these lands Green grabbing flourishes where land tenure is ambiguous, governance is weak, and market-driven development agendas prevail. Though these projects may appear environmentally sound on paper, their implementation often prioritizes profit and geopolitical display over genuine social or ecological benefit.

The first and most visible consequence of green grabbing is its direct assault on the livelihoods of rural populations—undermining SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger). Across the region, large-scale land acquisitions justified in the name of environmental protection or food security have displaced farmers, pastoralists, and fisherfolk from the lands that sustained them. These communities depend not only on farmland but also on grazing routes, wetlands, and coastal zones—spaces increasingly reclassified for "green" development. Whether through conservation fencing, solar installations, or land reclamation projects, the outcome is the same: people lose access to essential resources. Without viable alternatives, many are pushed into precarious wage labor or forced migration to overcrowded cities. This transition erodes local food systems and dismantles informal economies that once buffered communities against economic shocks. Any environmental or food production gains such projects achieve are outweighed by rising inequality, food insecurity, and the erosion of resilient traditional practices.

Beyond material loss, green grabbing deepens inequality and erodes social cohesion - undermining SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). The benefits of land-based development projects often accrue to national elites, foreign investors, or politically connected corporations. Communities at the margins—especially women, Indigenous peoples, and ethnic minorities—bear the greatest cost and are rarely included in planning or decision-making. The vulnerability of women is compounded when land rights rest on customary systems unrecognized by formal law. When land is seized or reallocated, these rights disappear - along with access to resources for fuel, water, and food production. The resulting loss of autonomy amplifies existing gender disparities, disempowering women within both households and communities. Meanwhile, unequal benefit-sharing mechanisms fuel tension and competition, pitting groups against one another and fracturing local social structures. These hidden costs of “green” development seldom make headlines, yet they shape everyday life and long-term resilience.

Ironically, projects designed to protect nature often inflict serious environmental harm - contradicting SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). Agricultural schemes promoted as climate-smart or sustainable frequently depend on heavy irrigation, placing additional pressure on already scarce water resources. In arid countries across the region, groundwater depletion and river diversion have worsened under the demands of export-oriented farming and desert greening projects. Similarly, renewable energy initiatives such as solar fields and wind farms require vast tracts of land. Their construction can destroy habitats, fragment wildfire corridors, and degrade fragile desert ecosystems. Industrial agriculture linked to land grabs adds further stress through chemical runoff, soil depletion, degradation, and water contamination. These ecological costs expose the contradictions at the heart of “green” development Without a grounded understanding of local ecosystems and community needs, green interventions risk generating new environmental burdens instead of alleviating existing ones.

The erosion of rights and institutions compounds the crisis. Green grabbing flourishes in settings where legal protections are weak and accountability mechanisms absent - undermining SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). Across the Arab region, many land laws remain shaped by colonial legacies that classified vast territories as state property, disregarding longstanding communal use. These legal grey zones are routinely exploited to advance land deals with minimal transparency. Corruption and elite capture aggravate the problem, enabling land transfers without consultation or compensation. In countries suffering from political instability, such as Libya, Yemen, and Iraq, land becomes a strategic resource for competing power brokers, intensifying conflict. Even in more stable contexts, the partnerships surrounding green investments are frequently exclusionary - top-down arrangements negotiated between governments and investors without the free, prior, and informed consent of affected communities. As trust in institutions erodes, protest and resistance rise, exposing the fragile foundations of these so-called sustainable partnerships.

Grounding this analysis in lived realities underscore the urgency of rethinking current trajectories. In Egypt, Bedouin communities have been displaced by state-led land reclamation projects framed as solutions to food insecurity and environmental degradation. In Jordan, the establishment of national parks has deprived stripped pastoralists of grazing lands essential to their livelihood. In Palestine, land appropriation intertwines with prolonged occupation and militarized control, rendering environmental narratives inseparable from political dispossession. These cases reveal that land grabbing is not merely a technical or economic matter but a profoundly political act with deep social, cultural, and ecological repercussion. Behind every reforestation fence or solar farm lies a story of someone pushed aside, unheard and unseen.

To move forward, the Arab region must abandon the illusion that “green” is always good. Genuine sustainability requires more than technological fixes or carbon accounting; it demands justice, participation, and accountability. This begins with recognizing and protecting customary land rights – particularly for women and marginalized groups. Governments and investors must embed the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) into law and practice, ensuring that communities have a meaningful voice in decisions affecting their lands and futures. Land governance must become more transparent, supported by accessible data, public oversight, and grievance mechanisms that provide real recourse. Development should be reimagined from the ground up - not imposed from above but co-created with the people it claims to serve.

In conclusion, land grabbing disguised as sustainability threatens not only the rights of individuals but the collective future of the Arab world. The SDGs offer a bold and necessary vision for human and planetary well-being, but they cannot be achieved through extractive, top-down models that displace the vulnerable. The region has the potential to lead in inclusive, rights-based approaches to environmental governance—if it reclaims sustainability from the forces of exclusion. By strengthening land rights movements, demanding accountability from public and private actors, and embedding equity into all green investments, we can begin to dismantle the illusion of “green” progress and build a future where sustainability truly includes everyone.

This article is based on a forthcoming paper by the same authors, titled "Green Grabbing in the Arab Region: Drivers and Implications for Sustainability.” It is part of a collaborative research project titled “Climate, Land, and Rights: The Quest for Social and Environmental Justice in the Arab Region” led by Mona Khechen and Sami Atallah.

From the same author

view allMore periodicals

view all-

12.19.25

المقالع تقضم الجبال: صناعة نظام اللاقانون

نزار صاغية, رين إبراهيمتضخّـم قطاع المقالع بعد عام 1990 بشكلٍ عشوائيّ، وتحوّل في معظمه إلى احتكارات تابعة لقوى نافذة تعمل خارج القانون. توثّـق هذه الورقة كيف تَشكّـل نظام اللاقانون في هذا القطاع، وما خلّفه من أضرار بيئيّة وماليّة واجتماعيّة، والدور الذي لعبته المواجهة القانونيّة–القضائيّة في إحداث أثر فعليّ على الأرض. ورقة بحثيّة من كتابة نزار صاغية ورين إبراهيم، ضمن مشروع “المناخ والأرض والحقّ” بالتعاون مع مبادرة سياسات الغد.

اقرأ -

11.21.25

وصفة لتبييض المسؤوليات في مجال الصرف الصحّي: الخلل في الصرف الصحي نظاميّ أيضًا

نزار صاغية, فادي إبراهيمتقدّم هذه الورقة خلاصةً دقيقة لتقرير ديوان المحاسبة الصادر في 27 شباط 2025 بشأن إدارة منظومة الصرف الصحّيّ في لبنان، مبيّنةً ما يعتريه من عموميّة وقصور، وما يكشفه ذلك من خللٍ بنيويّ في منظومة الرقابة والمحاسبة ومن الأسباب العميقة لتعثر محطّات معالجة الصرف الصحّي.

اقرأ -

04.24.25

اقتراح قانون إنشاء مناطق اقتصادية تكنولوجية: تكنولوجيا للبيع في جزر نيوليبرالية

المفكرة القانونية, مبادرة سياسات الغدتهدف هذه المسوّدة إلى تحقيق النمو الاقتصادي وخلق فرص عمل، غير أنّ تصميمها يصبّ في مصلحة قلّة من المستثمرين العاملين ضمن جيوب مغلقة، يستفيدون من إعفاءات ضريبية وكلفة أجور ومنافع أدنى للعاملين. وبالنتيجة، تُنشئ هذه الصيغة مساراً ريعيّاً فاسداً يُلحق ضرراً بإيرادات الدولة وبحقوق الموظفين وبالتخطيط الإقليمي (تجزئة المناطق). والأسوأ أنّ واضعي السياسات لا يُبدون أيّ اهتمام بتقييم أداء هذه الشركات أو مراقبته للتحقّق من تحقيق الغاية المرجوّة من المنطقة الاقتصاديّة.

اقرأ -

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

10.27.23eng

تضامناً مع العدالة وحق تقرير المصير للشعب الفلسطيني

-

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

09.09.23

بيان بشأن المادة 26 من مشروع قانون الموازنة العامة :2023

المادة ٢٦ من مشروع موازنات عام ٢٠١٣ التي اقرها مجلس الوزراء تشكل إعفاء لأصحاب الثروات الموجودة في الخارج من الضريبة النتيجة عن الأرباح والايرادات المتأتية منها تجاه الدولة اللبنانية. بينما يستمرون في الإقامة بشكل رسمي في لبنان ويتجنبون تكليفهم بالضرائب بالخارج بسبب هذه الإقامة. كما تضمنت المادة نفسها عفواً عاماً لهؤلاء من التهرب الضريبي. وكان مجلس الوزراء قد عمد إلى تعديل المادة 26 من المشروع ال مذكور، فيما كانت وزارة المالية تشددت على العكس من ذلك تماماً في تذكير بالمترتبات والنتائج القانونية والمالية الخطرة لأي تقاعس أو إخلال في تنفيذ الموجبات الضريبية ومنها الملاحقات الجزائية والحجز عىل الممتلكات و الاموال. واللافت أن هذا الإعفاء الذي يشمل ضرائب طائلة يأتي في الفترة التي الدولة هي بأمس الحاجة فيها إلى تأمين موارد تمكنها من إعادة سير مرافقها العامة ومواجهة الأزمة المالية والإقتصادية.

اقرأ -

08.24.23

من أجل تحقيق موحد ومركزي في ملف التدقيق الجنائي

في بيان مشترك مع المفكرة القانونية، مبادرة سياسات الغد، كلنا إرادة، وALDIC، نسلط الضوء على التقرير التمهيدي الذي أصدره Alvarez & Marsal حول ممارسات مصرف لبنان وأهميته كخطوة حاسمة نحو تعزيز الشفافية. ويكشف هذا التقرير عن غياب الحوكمة الرشيدة، وقضايا محاسبية، وخسائر كبيرة. إن المطلوب اليوم هو الضغط من أجل إجراء تدقيق جاد وموحد ومركزي ونشر التقرير رسمياً وبشكل كامل.

اقرأ -

07.27.23

المشكلة وقعت في التعثّر غير المنظّم تعليق دفع سندات اليوروبوندز كان صائباً 100%

-

05.17.23

حشيشة" ماكينزي للنهوض باقتصاد لبنان

-

01.12.23

وينن؟ أين اختفت شعارات المصارف؟

-

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب -

06.08.22eng

تطويق الأراضي في أعقاب أزمات لبنان المتعددة

منى خشن -

05.11.22eng

هل للانتخابات في لبنان أهمية؟

كريستيانا باريرا -

05.06.22eng

الانتخابات النيابية: المنافسة تحجب المصالح المشتركة