- عربي

-

- share

-

subscribe to our mailing listBy subscribing to our mailing list you will be kept in the know of all our projects, activities and resourcesThank you for subscribing to our mailing list.

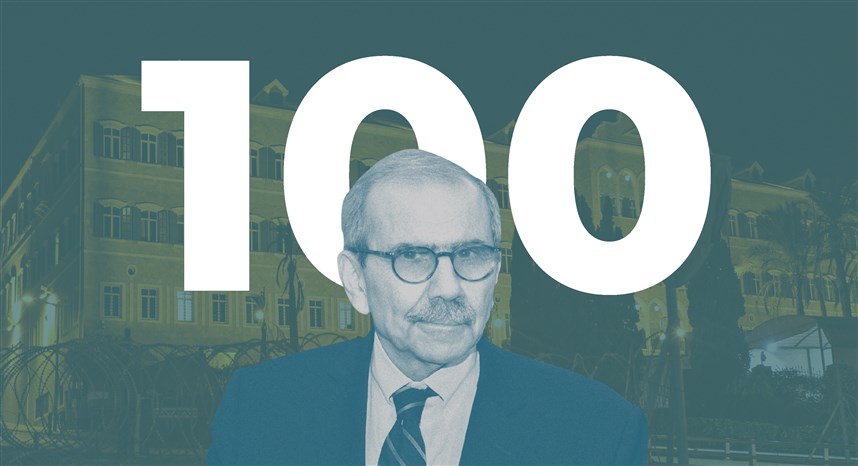

Salam’s Government First 100 Days: Early signals and structural constraints

Lebanon entered 2025 amid overlapping crises: economic collapse, the devastation of the 2024 war, and years of political paralysis. The national currency had lost nearly all its value, poverty engulfed more than 60% of households, and reconstruction needs were estimated at $14 billion. In this fragile context, a political breakthrough occurred: the election of Joseph Aoun as president on January 9, followed by Nawaf Salam’s formation of a fully mandated government on February 8—the first since 2021.

This report evaluates the Salam government’s first 100 days, benchmarking its performance against two yardsticks: (1) the record of Najib Mikati’s 2021 non-caretaker cabinet, and (2) progress on three national priorities essential to recovery—advancing IMF reforms, initiating reconstruction, and operationalizing the National Social Protection Strategy (NSPS).

The findings reveal a government that is more active and engaged than its predecessor, but still constrained by entrenched veto structures:

◊ Executive Activation: Salam’s cabinet convened 12 sessions (vs. Mikati’s 3) and issued 277 decrees and laws (vs. 141), including 35 regulatory texts (vs. 4). His government also made more appointments, accepted more international contributions, and issued fewer discretionary transfers and licenses.

◊ Regulatory Activity Without Depth: Salam’s regulatory footprint spanned 13 policy sectors, but most texts were procedural—clarifying procedures, adjusting compensations, or issuing temporary measures. The only structural reform was the amendment to the banking secrecy law.

◊ Administrative Recalibration: The government made 35 appointments (including 7 in defense and security, compared to none under Mikati), approved 107 contributions worth $14 million, and authorized fewer transfers and licenses. These shifts suggest greater external engagement and some restraint in clientelist practices, though motivations remain ambiguous.

◊ National Priorities Still Blocked:

- IMF Reforms: Salam reactivated key files (Bank Resolution Law, bank restructuring strategy, banking secrecy amendments) but avoided decisive steps such as bank audits, capital controls, and fiscal planning. Vetoes by banks, Banque du Liban, and allied political parties remain intact.

- Reconstruction: Despite appointing a ministerial committee, the government has made no substantive headway on reconstruction. There is still no national framework or implementation roadmap, leaving responses ad hoc and fragmented. Rubble removal which started months after the war is largely complete, but no government funding has been earmarked for rebuilding or compensation.

- Social Protection: The NSPS remains sidelined. Salam extended donor-funded, poverty-targeted programs rather than moving toward universal, rights-based coverage. This perpetuates Lebanon’s clientelist welfare regime, reinforced by donor preferences for humanitarian triage.

In short, Salam has reactivated executive machinery but has not yet translated activity into systemic reform.

The Salam government’s first 100 days demonstrate that Lebanon no longer suffers from outright executive paralysis. Cabinet meets regularly, decrees are issued, and institutions are staffed. This is not trivial. Yet activation has not become transformation.

The same veto players that have long blocked reform remain powerful. Banks and BDL shield financial interests from loss recognition. Reconstruction remains on hold, with no strategy or funding in place. Sectarian brokers and donors sustain a fragmented welfare system. Salam has worked around these constraints but not confronted them.

This leaves Lebanon at a political crossroads, with three potential trajectories:

1. Energetic Management of Stasis: Cabinet remains functional, output stays high, but reforms are shallow. Lebanon gains procedural governance but no structural change.

2. Reformist Confrontation: Salam leverages his legitimacy to challenge veto players—pushing for capital controls, fiscal strategy, and a national reconstruction plan. This risks political backlash but could reorient Lebanon’s trajectory.

3. Donor-Driven Conditionality: International actors impose stricter conditions, forcing selective reforms in banking or energy. This may unlock financing but risks deepening inequality and weakening sovereignty.

The first 100 days suggest that Salam is closer to energetic stasis than reformist rupture. Whether he evolves into a reformer willing to confront entrenched interests will determine not just his legacy but Lebanon’s path out of crisis.

From the same author

view all-

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب

More periodicals

view all-

02.18.26

تهديد مستشفى صلاح غندور: كيف تحاول إسرائيل نزع الحماية عن المرافق الصحّية في الجنوب؟

حسين شعبانيُظهر هذا التحقيق أنّ المسألة لم تعد تتعلّق بقدرة مستشفى على الصمود، بل بحدود المقبول قانونيًا وسياسيًا. فإذا سُمح بأن ينزع الغطاء المدني عن مرفق صحي بالاتهام وحده، يصبح أي مستشفى قابلًا للتجريد من حمايته بالكلام. وبهذا، تثبّت إسرائيل أنّ العمل الطبي في الجنوب اللبناني تحت التهديد بات قاعدة، لا استثناء. تم تحرير هذا المقال في إطار مشروع "مرصد إعادة الإعمار" الذي تنفّذه المفكّرة القانونية بالتعاون مع مبادرة سياسات الغد، استديو أشغال عامة، ومختبر المدن – بيروت.

اقرأ -

12.19.25

المقالع تقضم الجبال: صناعة نظام اللاقانون

نزار صاغية, رين إبراهيمتضخّـم قطاع المقالع بعد عام 1990 بشكلٍ عشوائيّ، وتحوّل في معظمه إلى احتكارات تابعة لقوى نافذة تعمل خارج القانون. توثّـق هذه الورقة كيف تَشكّـل نظام اللاقانون في هذا القطاع، وما خلّفه من أضرار بيئيّة وماليّة واجتماعيّة، والدور الذي لعبته المواجهة القانونيّة–القضائيّة في إحداث أثر فعليّ على الأرض. ورقة بحثيّة من كتابة نزار صاغية ورين إبراهيم، ضمن مشروع “المناخ والأرض والحقّ” بالتعاون مع مبادرة سياسات الغد.

اقرأ -

11.21.25

وصفة لتبييض المسؤوليات في مجال الصرف الصحّي: الخلل في الصرف الصحي نظاميّ أيضًا

نزار صاغية, فادي إبراهيمتقدّم هذه الورقة خلاصةً دقيقة لتقرير ديوان المحاسبة الصادر في 27 شباط 2025 بشأن إدارة منظومة الصرف الصحّيّ في لبنان، مبيّنةً ما يعتريه من عموميّة وقصور، وما يكشفه ذلك من خللٍ بنيويّ في منظومة الرقابة والمحاسبة ومن الأسباب العميقة لتعثر محطّات معالجة الصرف الصحّي.

اقرأ -

04.24.25

اقتراح قانون إنشاء مناطق اقتصادية تكنولوجية: تكنولوجيا للبيع في جزر نيوليبرالية

المفكرة القانونية, مبادرة سياسات الغدتهدف هذه المسوّدة إلى تحقيق النمو الاقتصادي وخلق فرص عمل، غير أنّ تصميمها يصبّ في مصلحة قلّة من المستثمرين العاملين ضمن جيوب مغلقة، يستفيدون من إعفاءات ضريبية وكلفة أجور ومنافع أدنى للعاملين. وبالنتيجة، تُنشئ هذه الصيغة مساراً ريعيّاً فاسداً يُلحق ضرراً بإيرادات الدولة وبحقوق الموظفين وبالتخطيط الإقليمي (تجزئة المناطق). والأسوأ أنّ واضعي السياسات لا يُبدون أيّ اهتمام بتقييم أداء هذه الشركات أو مراقبته للتحقّق من تحقيق الغاية المرجوّة من المنطقة الاقتصاديّة.

اقرأ -

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

10.27.23eng

تضامناً مع العدالة وحق تقرير المصير للشعب الفلسطيني

-

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

09.09.23

بيان بشأن المادة 26 من مشروع قانون الموازنة العامة :2023

المادة ٢٦ من مشروع موازنات عام ٢٠١٣ التي اقرها مجلس الوزراء تشكل إعفاء لأصحاب الثروات الموجودة في الخارج من الضريبة النتيجة عن الأرباح والايرادات المتأتية منها تجاه الدولة اللبنانية. بينما يستمرون في الإقامة بشكل رسمي في لبنان ويتجنبون تكليفهم بالضرائب بالخارج بسبب هذه الإقامة. كما تضمنت المادة نفسها عفواً عاماً لهؤلاء من التهرب الضريبي. وكان مجلس الوزراء قد عمد إلى تعديل المادة 26 من المشروع ال مذكور، فيما كانت وزارة المالية تشددت على العكس من ذلك تماماً في تذكير بالمترتبات والنتائج القانونية والمالية الخطرة لأي تقاعس أو إخلال في تنفيذ الموجبات الضريبية ومنها الملاحقات الجزائية والحجز عىل الممتلكات و الاموال. واللافت أن هذا الإعفاء الذي يشمل ضرائب طائلة يأتي في الفترة التي الدولة هي بأمس الحاجة فيها إلى تأمين موارد تمكنها من إعادة سير مرافقها العامة ومواجهة الأزمة المالية والإقتصادية.

اقرأ -

08.24.23

من أجل تحقيق موحد ومركزي في ملف التدقيق الجنائي

في بيان مشترك مع المفكرة القانونية، مبادرة سياسات الغد، كلنا إرادة، وALDIC، نسلط الضوء على التقرير التمهيدي الذي أصدره Alvarez & Marsal حول ممارسات مصرف لبنان وأهميته كخطوة حاسمة نحو تعزيز الشفافية. ويكشف هذا التقرير عن غياب الحوكمة الرشيدة، وقضايا محاسبية، وخسائر كبيرة. إن المطلوب اليوم هو الضغط من أجل إجراء تدقيق جاد وموحد ومركزي ونشر التقرير رسمياً وبشكل كامل.

اقرأ -

07.27.23

المشكلة وقعت في التعثّر غير المنظّم تعليق دفع سندات اليوروبوندز كان صائباً 100%

-

05.17.23

حشيشة" ماكينزي للنهوض باقتصاد لبنان

-

01.12.23

وينن؟ أين اختفت شعارات المصارف؟

-

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب -

06.08.22eng

تطويق الأراضي في أعقاب أزمات لبنان المتعددة

منى خشن -

05.11.22eng

هل للانتخابات في لبنان أهمية؟

كريستيانا باريرا -

05.06.22eng

الانتخابات النيابية: المنافسة تحجب المصالح المشتركة