- عربي

-

- share

-

subscribe to our mailing listBy subscribing to our mailing list you will be kept in the know of all our projects, activities and resourcesThank you for subscribing to our mailing list.

Contested Ground: Why land grabbing is accelerating in the Arab World

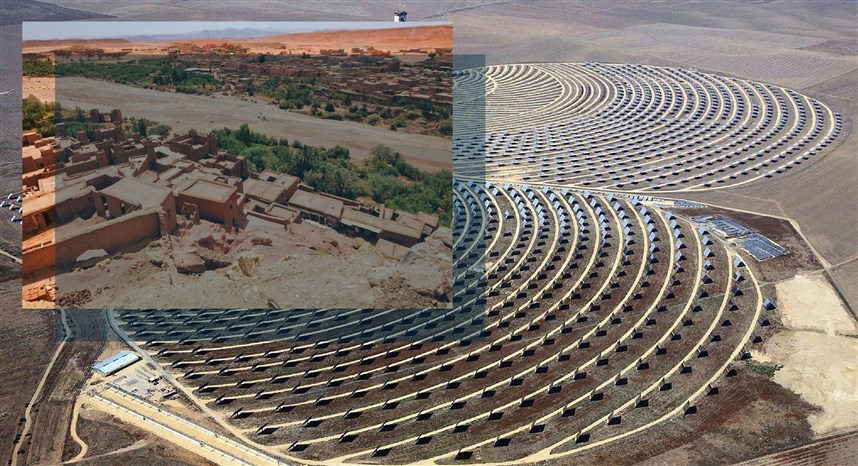

In Ouarzazate, Morocco, Amazigh agro-pastoralist communities awoke to find hundreds of hectares of their ancestral grazing lands fenced off and transformed into a state-backed solar mega-plant, The Noor complex. Though celebrated as a green energy breakthrough, the reclassification was imposed without consultation or compensation, erasing customary land claims and obstructing traditional mobility across the landscape. Communities lost access to their own grazing routes and saw their water resources diverted toward the project. Overnight, the land that sustained their food and incomes was taken away. Their story is far from unique. It reflects a broader pattern across the Arab world, where competing imperatives of economic growth, environmental urgency, and political ambition are converging to reshape land ownership and access.

This article examines the complex forces driving land grabbing in the Arab region. It argues that land, has become a contested and highly politicized commodity. What sets the current wave of acquisitions apart is the growing entanglement of economic development ambitions, social vulnerabilities, institutional weaknesses, and environmental pressures. By tracing how these dynamics intersect, the article shows why land grabbing is accelerating and why its underlying drivers has become urgent. At the heart of the phenomenon lies a powerful set of economic motivations that shape, and are reinforced by, these broader social and political conditions.

In Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, governments are racing to diversify their economies, reduce dependence on oil and gas, and secure stronger positions in global markets. In other Arab countries, including Morocco, Egypt, and Jordan, land pressures stem more from tourism development, large-scale agricultural investments, and infrastructure expansion Together, these trends generate an insatiable demand for land to host mega-projects, new smart cities, industrial zones, tourism resorts, large-scale farms, and renewable energy facilities. Cast as symbols of modernity and progress, such projects nonetheless require vast tracts of land - often in areas where rural communities have long relied on subsistence farming or pastoralism.

Global dynamics intensify this pressure. In moments of food or energy crisis, such as the 2007–2008 food price spike or more recent geopolitical disruptions, land acquires a new strategic importance. Wealthy but land-scarce countries seek to secure agricultural supply chains abroad, frequently targeting territories perceived as underutilized. Meanwhile, speculative investors increasingly view land as a safe, appreciating asset – a hedge against volatility. The result is a convergence of public and private, national and global interests, all bearing down with mounting intensity on available land.

Yet land grabs do not occur in a vacuum. They are enabled by vulnerabilities embedded in the region’s land tenure systems. In many Arab countries, especially in rural or marginalized areas, land rights are governed by customary norms rather than formal documentation. Because these are rarely recognized by national law, communities find themselves in precarious legal positions. When governments or companies appropriate land for development, residents often lack the legal standing to to contest the seizure, even if their ties stretch back generations. The roots of this problem lie in colonial policies, which classified unregistered land as state property – a framework largely preserved by postcolonial governments. Today, the legacy is a a fragmented and ambitious system in which the state can legally claim land in active use by local populations. This ambiguity enables powerful actors to exploit legal loopholes, displacing communities without meaningful consultation or compensation.

Political dynamics further entrench this imbalance. Development priorities are often framed as national imperatives, and governments, eager to attract foreign investment and accelerate growth—often prioritize large-scale projects over local rights. In many cases, land grabbing is facilitated by institutional opacity and weak enforcement of the rule of law. Corruption within land administration systems enables deals to occur behind closed doors, with little public scrutiny. In conflict-affected countries, the situation is even more acute. Where governance structures have collapsed or are deeply contested, powerful groups, including armed factions or local elites, may seize land under the cover of political instability. The legacy of centralized land control, inherited from colonial land laws, allows states to justify mass reallocations of land with minimal legal challenge. Meanwhile, international financial institutions and donor agencies often push for market-led development and land liberalization, further pressuring governments to open land markets without fully assessing the social consequences. The outcome is a political economy of land where power, not justice, determines access and control.

Ironically, environmental pressures are now playing a central role in driving land grabs, often justified in the name of sustainability. As the Arab region confronts intensifying climate threats, governments and investors increasingly promote large-scale environmental projects aimed at adaptation and mitigation. These include reforestation campaigns, water harvesting schemes, and, most notably, renewable energy infrastructure such as solar farms and wind parks. While these projects are essential to long-term resilience, they also require massive amounts of land often located in remote or ecologically sensitive areas. In many cases, the land targeted sustains communities whose livelihoods depend on grazing, foraging, or small-scale farming. Despite the appearance of being empty or underused, these landscapes are deeply integrated into local social and ecological systems. When they are appropriated for environmental initiatives without adequate planning, they create new layers of dispossession and conflict. The paradox is clear: efforts to address environmental degradation can, if poorly governed, produce social and ecological harm.

Taken together, these economic, social, political, and environmental factors form a tightly woven web that explains the rise of land grabbing in the Arab world. No single factor operates in isolation. Rather, they reinforce one another in a self-perpetuating cycle. A development project justified by economic necessity may proceed on land acquired through weak legal frameworks, approved by institutions vulnerable to corruption, and framed as a response to climate change. Each thread connects to the next, forming a structure that is remarkably resilient to reform and resistant to public scrutiny and accountability.

Understanding this web is a vital first step toward dismantling it. Addressing land grabbing in the Arab region requires more than piecemeal reforms or technical fixes. It demands a transformative approach to land governance, one that centers community rights, enforces transparency, and ensures that sustainability efforts do not come at the cost of justice. Governments must recognize and formalize customary land rights, especially for rural and indigenous communities. Legal systems must be restructured to prevent unchecked state appropriation and mandate free, prior, and informed consent for all land acquisitions. Civil society must be empowered to monitor land deals, and accessible grievance mechanisms should be created and enforced to protect those affected. Above all, the region must shift from a model of development that concentrates land and power in the hands of a few to one that more equitably distributes opportunity and treats land as the foundation of both ecological health and human dignity. Land is not just a resource, it is a space of identity, belonging, and survival. If the Arab world is to navigate the urgent challenges of climate change, food insecurity, and political instability, it must start with reimagining how land is governed, shared, and valued. Otherwise, the costs of unchecked land appropriation will be borne not only by those displaced today, but by generations yet to come.

This article is part of a collaborative research project titled “Climate, Land, and Rights: The Quest for Social and Environmental Justice in the Arab Region” led by Mona Khechen and Sami Atallah.

From the same author

view allMore periodicals

view all-

12.19.25

المقالع تقضم الجبال: صناعة نظام اللاقانون

نزار صاغية, رين إبراهيمتضخّـم قطاع المقالع بعد عام 1990 بشكلٍ عشوائيّ، وتحوّل في معظمه إلى احتكارات تابعة لقوى نافذة تعمل خارج القانون. توثّـق هذه الورقة كيف تَشكّـل نظام اللاقانون في هذا القطاع، وما خلّفه من أضرار بيئيّة وماليّة واجتماعيّة، والدور الذي لعبته المواجهة القانونيّة–القضائيّة في إحداث أثر فعليّ على الأرض. ورقة بحثيّة من كتابة نزار صاغية ورين إبراهيم، ضمن مشروع “المناخ والأرض والحقّ” بالتعاون مع مبادرة سياسات الغد.

اقرأ -

11.21.25

وصفة لتبييض المسؤوليات في مجال الصرف الصحّي: الخلل في الصرف الصحي نظاميّ أيضًا

نزار صاغية, فادي إبراهيمتقدّم هذه الورقة خلاصةً دقيقة لتقرير ديوان المحاسبة الصادر في 27 شباط 2025 بشأن إدارة منظومة الصرف الصحّيّ في لبنان، مبيّنةً ما يعتريه من عموميّة وقصور، وما يكشفه ذلك من خللٍ بنيويّ في منظومة الرقابة والمحاسبة ومن الأسباب العميقة لتعثر محطّات معالجة الصرف الصحّي.

اقرأ -

04.24.25

اقتراح قانون إنشاء مناطق اقتصادية تكنولوجية: تكنولوجيا للبيع في جزر نيوليبرالية

المفكرة القانونية, مبادرة سياسات الغدتهدف هذه المسوّدة إلى تحقيق النمو الاقتصادي وخلق فرص عمل، غير أنّ تصميمها يصبّ في مصلحة قلّة من المستثمرين العاملين ضمن جيوب مغلقة، يستفيدون من إعفاءات ضريبية وكلفة أجور ومنافع أدنى للعاملين. وبالنتيجة، تُنشئ هذه الصيغة مساراً ريعيّاً فاسداً يُلحق ضرراً بإيرادات الدولة وبحقوق الموظفين وبالتخطيط الإقليمي (تجزئة المناطق). والأسوأ أنّ واضعي السياسات لا يُبدون أيّ اهتمام بتقييم أداء هذه الشركات أو مراقبته للتحقّق من تحقيق الغاية المرجوّة من المنطقة الاقتصاديّة.

اقرأ -

02.05.25eng

أزمة لبنان بنيوية، لا وزارية

سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

10.15.24eng

لا عدالة مناخية في خضمّ الحروب

منى خشن, سامي عطاالله -

06.14.24

عطاالله: التدّخل السياسي عقبة أمام تطوّر الإدارة العامة

سامي عطااللهمقابلة مع مدير مبادرة سياسات الغد الدكتور سامي عطاالله أكد أن "التدخل السياسي هو العقبة الرئيسية أمام تطور الإدارة العامة"، وشدد على أن دور الدولة ووجودها ضروريان جدًا لأن لا وجود للاقتصاد الحر أو اقتصاد السوق من دونها"

اقرأ -

10.27.23eng

تضامناً مع العدالة وحق تقرير المصير للشعب الفلسطيني

-

09.21.23

مشروع موازنة 2023: ضرائب تصيب الفقراء وتعفي الاثرياء

وسيم مكتبي, جورجيا داغر, سامي زغيب, سامي عطاالله -

09.09.23

بيان بشأن المادة 26 من مشروع قانون الموازنة العامة :2023

المادة ٢٦ من مشروع موازنات عام ٢٠١٣ التي اقرها مجلس الوزراء تشكل إعفاء لأصحاب الثروات الموجودة في الخارج من الضريبة النتيجة عن الأرباح والايرادات المتأتية منها تجاه الدولة اللبنانية. بينما يستمرون في الإقامة بشكل رسمي في لبنان ويتجنبون تكليفهم بالضرائب بالخارج بسبب هذه الإقامة. كما تضمنت المادة نفسها عفواً عاماً لهؤلاء من التهرب الضريبي. وكان مجلس الوزراء قد عمد إلى تعديل المادة 26 من المشروع ال مذكور، فيما كانت وزارة المالية تشددت على العكس من ذلك تماماً في تذكير بالمترتبات والنتائج القانونية والمالية الخطرة لأي تقاعس أو إخلال في تنفيذ الموجبات الضريبية ومنها الملاحقات الجزائية والحجز عىل الممتلكات و الاموال. واللافت أن هذا الإعفاء الذي يشمل ضرائب طائلة يأتي في الفترة التي الدولة هي بأمس الحاجة فيها إلى تأمين موارد تمكنها من إعادة سير مرافقها العامة ومواجهة الأزمة المالية والإقتصادية.

اقرأ -

08.24.23

من أجل تحقيق موحد ومركزي في ملف التدقيق الجنائي

في بيان مشترك مع المفكرة القانونية، مبادرة سياسات الغد، كلنا إرادة، وALDIC، نسلط الضوء على التقرير التمهيدي الذي أصدره Alvarez & Marsal حول ممارسات مصرف لبنان وأهميته كخطوة حاسمة نحو تعزيز الشفافية. ويكشف هذا التقرير عن غياب الحوكمة الرشيدة، وقضايا محاسبية، وخسائر كبيرة. إن المطلوب اليوم هو الضغط من أجل إجراء تدقيق جاد وموحد ومركزي ونشر التقرير رسمياً وبشكل كامل.

اقرأ -

07.27.23

المشكلة وقعت في التعثّر غير المنظّم تعليق دفع سندات اليوروبوندز كان صائباً 100%

-

05.17.23

حشيشة" ماكينزي للنهوض باقتصاد لبنان

-

01.12.23

وينن؟ أين اختفت شعارات المصارف؟

-

10.12.22eng

فساد في موازنة لبنان

سامي عطاالله, سامي زغيب -

06.08.22eng

تطويق الأراضي في أعقاب أزمات لبنان المتعددة

منى خشن -

05.11.22eng

هل للانتخابات في لبنان أهمية؟

كريستيانا باريرا -

05.06.22eng

الانتخابات النيابية: المنافسة تحجب المصالح المشتركة